By Bob Hicks

The new baby arrived the other day, and it’s a whopper: 12.2 inches long, 10.3 inches across, almost 2 inches thick and 8.5 pounds. It came after a labor so long you don’t want to contemplate it, but when it finally arrived it came out handsome and beautifully illustrated.

The new baby arrived the other day, and it’s a whopper: 12.2 inches long, 10.3 inches across, almost 2 inches thick and 8.5 pounds. It came after a labor so long you don’t want to contemplate it, but when it finally arrived it came out handsome and beautifully illustrated.

Coffee tables across America have been put on alert: Brace yourselves. The new kid’s big.

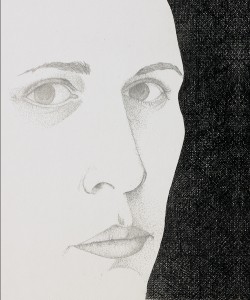

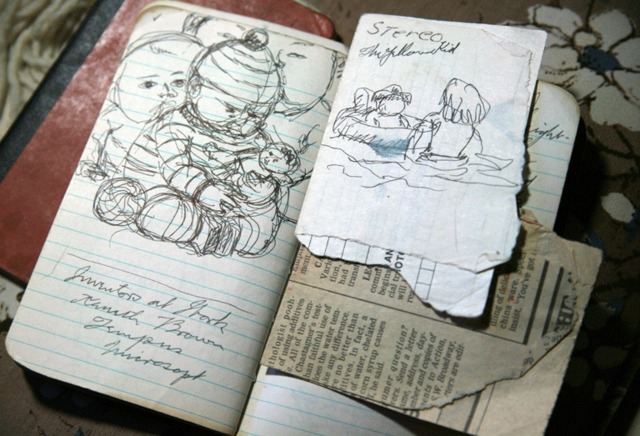

Beth Van Hoesen: Catalogue Raisonné of Limited-Edition Prints, Books, and Portfolios has just been published by Hudson Hills Press, in association with the Oakland Museum of California, Racine Art Museum in Wisconsin, and the University Museums, Iowa State University, Ames.

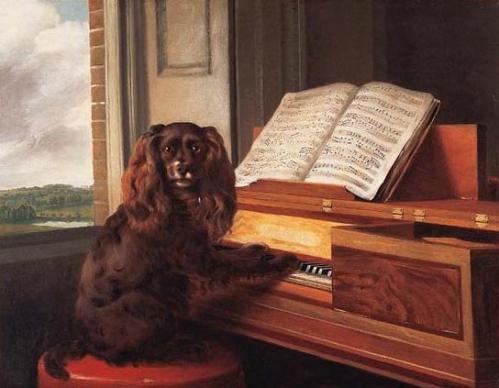

Van Hoesen, who died late last year at age 84, was a longtime San Francisco artist who specialized in printmaking, taking as her subject the small things of life: animals, insects, flowers, babies, fruits and vegetables, dolls, portraits. She also drew and made prints of a lot of nudes — a portfolio of her male nudes was one of the first projects published by the Bay Area’s fabled Crown Press — and completed a little-known but highly intriguing series of portraits of people from the punk scene in San Francisco’s Castro District, near the old firehouse where Van Hoesen and her husband, the tapestry designer and watercolorist Mark Adams, lived and worked for close to 50 years. Physical veracity was extremely important to her, and in the best of her work that attention to truthfulness was much more than skin-deep.

I wrote what became the catalogue’s lead essay, Becoming Perfect, which is primarily about Van Hoesen’s drawings, both finished pieces and preparatory drawings for her hundreds of prints. In the end, her work is really about the magic of the line, and getting it right.

Pacific Northwest College of Art

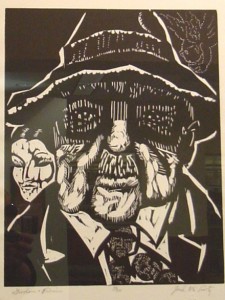

Pacific Northwest College of Art I never really knew Jack, although I talked with him several times. In the 1970s and ’80s I used to frequent the old Image Gallery that he and his wife Barbara ran downtown, a pioneer space that included Inuit and Mexican and other “folk” art in addition to McLarty’s own brand of homegrown modernism — pretty much no one of note was as intensely a Portland artist as he was. I reviewed a couple of his shows, briefly, and always enjoyed the long chatty letters that Barbara sent out, blends of professional marketing and family updates. I sometimes thought of McLarty as a sort of flip-side

I never really knew Jack, although I talked with him several times. In the 1970s and ’80s I used to frequent the old Image Gallery that he and his wife Barbara ran downtown, a pioneer space that included Inuit and Mexican and other “folk” art in addition to McLarty’s own brand of homegrown modernism — pretty much no one of note was as intensely a Portland artist as he was. I reviewed a couple of his shows, briefly, and always enjoyed the long chatty letters that Barbara sent out, blends of professional marketing and family updates. I sometimes thought of McLarty as a sort of flip-side

David Cooper/OSF

David Cooper/OSF Judith H. Dobrzynski passes along

Judith H. Dobrzynski passes along  Jenny Graham/OSF

Jenny Graham/OSF T. Charles Erickson/OSF

T. Charles Erickson/OSF T. Charles Erickson/OSF

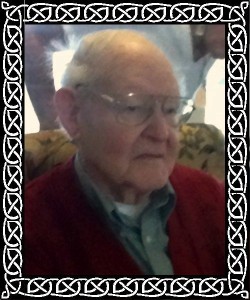

T. Charles Erickson/OSF We pause for a long moment of reflection, love, and respect. Without Irby Hicks there would be no Art Scatter, not just because without him we would never have been born, but also because he instilled in his seven children the love of language and story that is crucial to the forming of any writer. Three of his children became professional writers. The other four are devoted readers.

We pause for a long moment of reflection, love, and respect. Without Irby Hicks there would be no Art Scatter, not just because without him we would never have been born, but also because he instilled in his seven children the love of language and story that is crucial to the forming of any writer. Three of his children became professional writers. The other four are devoted readers. I vividly recall the time he put a chicken on the chopping block and lopped off its head. The decapitated bird rose up, flapped its wings, and flew across the low-lying garage, finally flopping to the ground on the other side. One sister recalls this. No one else does. So my sister and I wonder: Was this somebody else’s story that we somehow transposed to Dad? I remember the time I came home from school and encountered a whole hog’s head staring up from the bathtub: Dad had acquired it, and until he had time to strip it down, there was no place else to store it. No one else remembers that one. Did it happen? One thing’s true: the garden. That large, lush garden that for years flourished so magnificently. Maybe I think of food because it nourishes, and Dad nourished my own life. I am, in many ways, what he planted.

I vividly recall the time he put a chicken on the chopping block and lopped off its head. The decapitated bird rose up, flapped its wings, and flew across the low-lying garage, finally flopping to the ground on the other side. One sister recalls this. No one else does. So my sister and I wonder: Was this somebody else’s story that we somehow transposed to Dad? I remember the time I came home from school and encountered a whole hog’s head staring up from the bathtub: Dad had acquired it, and until he had time to strip it down, there was no place else to store it. No one else remembers that one. Did it happen? One thing’s true: the garden. That large, lush garden that for years flourished so magnificently. Maybe I think of food because it nourishes, and Dad nourished my own life. I am, in many ways, what he planted.