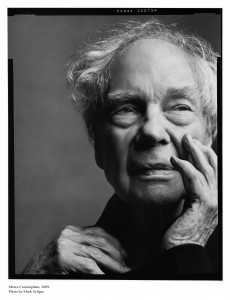

Dance critic and historian Martha Ullman West has spent a lot of time thinking about Merce Cunningham, the great 20th century dancer and choreographer who rethought what dance means by introducing chance as a primary element in the mix. Cunningham, who was born and raised 90 miles from Portland in the small town of Centralia, Wash., died July 26 at age 90. Martha considers, among other things, the effect that the Pacific Northwest had on Cunningham’s art.

__________________________________________________________________

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

He died in New York on Sunday, July 26, at his home in Greenwich Village. In his obituary for the New York Times, Alastair Macaulay, who is working on a book on Cunningham, called him “always a creature of New York.”

That’s not untrue, at least from 1939 on, when Cunningham joined Martha Graham‘s company. But it’s only part of the story.

Merce, in fact, was one of ours. So was Robert Joffrey. So are Trisha Brown and Mark Morris, who, thank God, are still around. All are natives of the Pacific Northwest, specifically Washington State.

I believe that Merce’s use of space, his sense of infinite possibility, his connection to nature, his conviction that you can do anything that pleases you on stage as long as it works aesthetically, came from the ethos of this part of the world. You see those elements in the poetry of Gary Snyder, who like Merce and composer John Cage, Merce’s long-term partner in life and art, was influenced by Zen thinking. You see them, certainly, in the work of Trisha Brown.

And, to bring it home to Portland, you see it in the choreography and technique of Mary Oslund, who studied with Cunningham and several members of his company, including the late Viola Farber. Oslund remembers being at dinner with Merce when White Bird presented the company (which, God love them, they did twice, in 2001 and 2004). Merce talked with her about Farber, Mary says, in his “diminutive and humble way.”

“He gave us a lot of permission,” Susan Banyas told dance maker Gregg Bielemeier when she heard the news of Merce’s death.

Truth be told, Merce and such collaborators as Cage, Robert Rauschenberg and David Tudor gave scores of choreographers, composers, painters, and audience members permission to free themselves of academic constraints. Merce helped free them from obedience to 19th century theatrical principles and fidelity to specific forms: classical ballet, traditional modernism, representational art, storytelling, the calculated melding of music and dance, lighting and design.

What appeared on stage in Merce’s work looked like integrated work, as exemplified by his company’s 2001 concert at Portland’s Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall. Yet certainly in most cases music, decor and choreography were created separately, without consultation among the collaborators, and the dancers did not hear the music until the dress rehearsal.

What appeared on stage in Merce’s work looked like integrated work, as exemplified by his company’s 2001 concert at Portland’s Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall. Yet certainly in most cases music, decor and choreography were created separately, without consultation among the collaborators, and the dancers did not hear the music until the dress rehearsal.

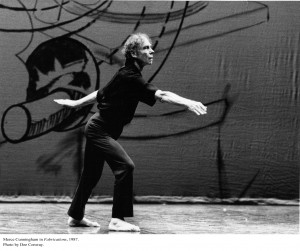

The program at the Schnitz opened with the 1958 Summerspace, scenery and costumes by Rauschenberg, music by Morton Feldman, the dancers schooled in Cunningham’s vocabulary, which is classically based, dancing in a dappled environment reminiscent of the woods on a hot summer day.

For Pond Way, which premiered in 1998 with music by Brian Eno and design by Roy Lichtenstein, Cunningham comments in the superb PBS American Masters Merce Cunningham: A Lifetime in Dance that he wanted fluid movement, and thought of going to the lake when he was a child in Centralia, Wash., hence the title. (That American Masters show is available on DVD; go get it immediately.)

The closer was a doozy: Rain Forest, with music by Tudor and decor by Andy Warhol, concluded with the dancers heaving the silvery helium balloons that were part of the decor into the audience. By that time some audience members had walked out. Just why is mystifying, for this was vintage Merce, classic Merce, gorgeous Merce.

Cunningham was traveling with the company that time, and the dancers were rehearsing and taking company class in BodyVox‘s old space. Merce, at 82, was suffering pretty badly from arthritis (which hadn’t stopped him from performing with Baryshnikov in Occasion Piece two years before, and according to several critics, upstaging him to boot) and BodyVox’s Jamey Hampton took him up to the studio in the freight elevator.

This was the only time I ever talked with Cunningham, standing next to him as he watched the dancers warming up. I told him I had never reviewed his work, and that I really didn’t want to.

This was the only time I ever talked with Cunningham, standing next to him as he watched the dancers warming up. I told him I had never reviewed his work, and that I really didn’t want to.

“Why?” he asked, looking surprised.

“Because you’ve said it all,” I answered. “I really have nothing to add.”

He smiled and joined the dancers at the barre, gently, slowly, bending his knees in plie, this man who’d been known for his spectacular jump.

Since then I’ve seen the work he did with motion-capture technology — including the extraordinary Biped, in which the dancers perform with the life forms Merce used to choreograph when he could no longer do it on his own body, plus Interscape and Fluid Canvas, which were performed here in 2004 — and I find I have more to say than I thought I did at that time.

But more in admiration than explanation. Admiration for the constant quest for information, the openness to new ideas and new technologies, the man’s sheer genius for observation and translation of that observation into movement, for the depth of his ideas and his commitment to his art and other artists.

Go, I want to say to today’s young, middle-aged and old so-called creatives, and do likewise.

Liberate yourselves from trends, from grantspeak, from marketing constructs and self-consciousness.

At the end of the day Merce did, indeed, say it all: “Dancing for me is movement in time and space. Its possibilities are bound only by our imagination and our two legs.”