I’ve been thinking about Wordstock, Portland’s annual orgy of wordsmithery, which runs Oct. 10-11 at the Oregon Convention Center.

Lots and lots of good writers will be showing up: Glad, for instance, to see that Sherman Alexie‘s finally making the party, and so soon after nabbing the National Book Award for his first young-adult novel, the wrenching and funny Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

Lots and lots of good writers will be showing up: Glad, for instance, to see that Sherman Alexie‘s finally making the party, and so soon after nabbing the National Book Award for his first young-adult novel, the wrenching and funny Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

There’s a lot more to Alexie’s book than its few short passages on the art of manly self-delight, but those glowing paragraphs are going to help keep Part-Time Indian in a sort of Holden Caulfield furtive page-flipping, perennial-sales mode for a long time to come.

And I’ve been thinking about another annual people’s celebration of the arts, Portland Open Studios, which runs the same weekend as Wordstock and one more, too — Oct. 10, 11, 17 and 18. Entering its tenth year (Wordstock’s half that age) Portland Open Studios throws the doors open to 100 artists’ studios across the city and invites anyone who’s interested for a tour of the stage shop behind the scenes. For people struck dumb with the dreaded Fear of Galleries, this can be a reassuring and fascinating way to get inside the visual arts scene, to see the everyday workings of everyday working artists, to actually talk with the artists about what they see and think and do.

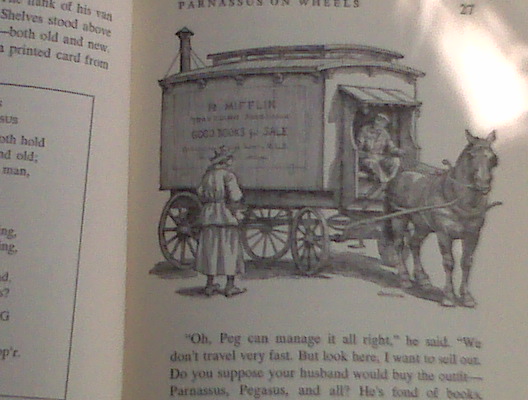

So then I came across the images above and below from Tacoma sculptor Holly A. Senn‘s just-closed installation at Portland’s 23 Sandy Gallery, and the thought struck me: Senn’s work, which I unhappily missed, bridges the gap between Wordstock and Portland Open Studios.

Senn, who is a librarian as well as a visual artist, makes forests and giant seed pods from abandoned books, reimagining them into fresh new life: words become art become words.

“My art investigations,” Senn writes, “are inextricably intertwined with my work as a virtual reference librarian at Pacific Lutheran University where, while surrounded by books, I interact with patrons who prefer digital resources. As I cut, rip, realign and glue, I reflect on each new generations’ collective erasure of some element of the past and its casting of new ideas into the future. My work is as ephemeral and fleeting as ideas committed to paper.”

What are we in the process of collectively erasing?

23 Sandy’s current show, Broadsided! The Intersection of Art and Literature, seems to be bridging the art/word gap, too. It’s a juried exhibition of broadsides, those fascinating blends of letterpress art and information, by 34 artists from across the United States and Australia. The show stays up through Oct. 31, so there’s plenty of time to see what’s up.

**********************************

Ballyhoo hullabaloo: Out Oregon City way, in a town that’s ancient by Oregon’s thinly planted European standards, people know a thing or two about tradition. So maybe it makes sense that an old-fashioned play like Alfred Uhry’s The Last Night of Ballyhoo, a drawing-room dramedy that won the Tony Award for best play of 1997 and even then seemed a stylistic relic of a lost theatrical golden age, is on stage at Clackamas Repertory Theatre, the small professional company that performs at the O.C.’s Clackamas Community College.

Uhry’s play, set among the Jewish gentry of Atlanta in 1939, is about the layers of prejudice among the South’s several waves of Jewish immigrants. I’ve never been a fan of Uhry’s breakout play, Driving Miss Daisy — can’t get past the social implications of the sassy rich Southern woman and her devotedly longsuffering black servant — but I like Ballyhoo quite a bit, and the Rep’s production does well by it. My short review ran in Monday’s Oregonian. You can see the longer, more expansive version on Oregon Live.

I called it up. And read it aloud. We laughed some more. And everyone urged me to post it as a comment. I still wasn’t sure, but the wine was flowing and the tree was sparkling and the company was cheery and did I mention the wine?

I called it up. And read it aloud. We laughed some more. And everyone urged me to post it as a comment. I still wasn’t sure, but the wine was flowing and the tree was sparkling and the company was cheery and did I mention the wine? Portland Taiko is 15 years old, which in people time would mean it’s itching to get a driver’s license but in Arts Group Years means it’s long out of those troublesome teen years and well into its energetic adulthood. Still growing, still learning, but with the assurance that comes with the self-confidence that comes with mastery of key skills.

Portland Taiko is 15 years old, which in people time would mean it’s itching to get a driver’s license but in Arts Group Years means it’s long out of those troublesome teen years and well into its energetic adulthood. Still growing, still learning, but with the assurance that comes with the self-confidence that comes with mastery of key skills. It’ll be at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 7, in the college’s Vollum Lecture Hall, and it’s free.

It’ll be at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 7, in the college’s Vollum Lecture Hall, and it’s free. Today, after a matinee performance of All’s Well That Ends Well, the extended Scatter Family leaves Ashland and the

Today, after a matinee performance of All’s Well That Ends Well, the extended Scatter Family leaves Ashland and the

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind.

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind. In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose

In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose  Niel DePonte has another idea, and you can read about it on this morning’s Oregonian editorial page, under the headline

Niel DePonte has another idea, and you can read about it on this morning’s Oregonian editorial page, under the headline  No computer screens today, though. On most Sunday mornings Destino offers a bonus: Guitarist John Dodge sits on a stool in the corner by the kids’ toys, small amp propped on a chair beside him, and gives the French blend and bagels a musical setting. It’s melodic, and just the right decibel, and a bit Robert Browning-ish in its simple elegance: All’s right with the world.

No computer screens today, though. On most Sunday mornings Destino offers a bonus: Guitarist John Dodge sits on a stool in the corner by the kids’ toys, small amp propped on a chair beside him, and gives the French blend and bagels a musical setting. It’s melodic, and just the right decibel, and a bit Robert Browning-ish in its simple elegance: All’s right with the world.

PNCA at 100: Two good pieces on the

PNCA at 100: Two good pieces on the Mr. Salinger does know the legal profession, and in pursuit of his vaunted rights has made liberal use of it over the years. The New York Times reports

Mr. Salinger does know the legal profession, and in pursuit of his vaunted rights has made liberal use of it over the years. The New York Times reports