Update: Photographer David Paul Bayles’ free lecture at 23 Sandy Gallery, discussed below, has been postponed a week. Originally set for this Saturday, April 18, it’s been rescheduled for 6 p.m. next Saturday, April 25, at the gallery, 623 N.E. 23rd Ave., Portland.

A person of my close acquaintance (all right, she’s my daughter) has been laid off from a job she detests — indeed, a job which for at least a couple of years she’s harbored elaborate fantasies of quitting in grand-tragedian style. They beat her to the punch. She outlasted many of her friends at this Dilbertian company, who, she says, have created a greeting for new members of the formerly-employed-by-idiots club.

A person of my close acquaintance (all right, she’s my daughter) has been laid off from a job she detests — indeed, a job which for at least a couple of years she’s harbored elaborate fantasies of quitting in grand-tragedian style. They beat her to the punch. She outlasted many of her friends at this Dilbertian company, who, she says, have created a greeting for new members of the formerly-employed-by-idiots club.

“Congratudolences,” they say, and they mean both halves of the word.

A person of my even closer acquaintance (all right, she’s my wife) is leaving a job she loves, because as a part-time worker she’s in recurring jeopardy of being laid off, and the industry in which she works, while a noble one, seems sadly to be circling the drain of no return.

Tim-berrrrr!

The clear-cut just keeps getting closer, doesn’t it? If a tree falls in the middle of a forest and it smacks you upside the head, are you too dazed to feel it?

For our daughter, the timing isn’t too bad. In fact, it could scarcely be better. In the fall she’s off to seven years of grad school, maybe in Tucson, maybe in Austin, probably in Seattle, from which she’ll emerge with a Ph.D. in Gothic literature and perhaps a whole new set of occupational challenges.

For my wife, who departs her long-loved job with a modest yet under the circumstances generous severance agreement that will keep the wolf from the door for a year even if if she doesn’t find another source of income between now and then, this is what they call an opportunity. For reinvention, for redirection, for a fresh start, for the edge-of-the-seat thrill of making things up as she goes along. And she’s embracing it, almost cheerfully. More control of her schedule. A chance to freelance. Time at the beach. Is this what they mean by the “creative economy”? Among her many skills, which include organizational abilities that leave me fairly gasping for air, my mate is an excellent writer, with a rare and subversive wit. Perhaps that will make her fortune, as it has for us here at Art Scatter’s gilded world headquarters, where we’re envied by all as the Warren Buffetts of the blogosphere.

I think we’ll plant a garden this year. Tomatoes, herbs, lettuce, maybe a few cukes … does asparagus grow OK in a parking strip? Actually, in a weird way, this could be fun.

*******************

I like the intelligence and energy at 23 Sandy Gallery, an eastside Portland gallery I got to know when I wrote a story about its recent exhibit of on-demand fine photography books. The gallery emphasizes photography, hand-made books and graphic arts, all areas that are congenial to my own interests, and owner Laura Russell has a smart eye and an open mind.

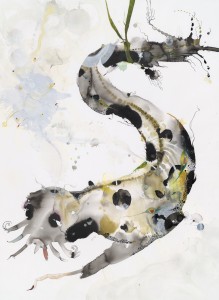

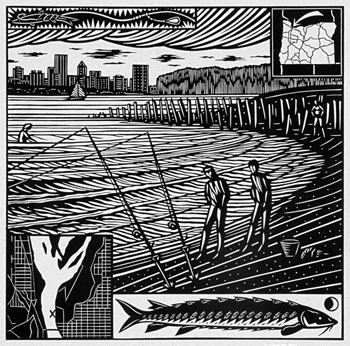

This month the gallery is showing photos by David Paul Bayles of trees being felled — that’s his Falling Tree #3, which I shamelessly employed for metaphorical purposes, pictured above. And although I haven’t seen it yet, the show seems to suggest some insights into the world of tough economics as it’s been known in the Pacific Northwest for a long time. Here’s how the gallery’s Web site describes it:

From his early days as a logger in the Sierra Nevada Mountains to his present home on Dreaming Forest Farm outside Corvallis, David Paul Bayles has lived and worked from, with and in the trees. Of his many bodies of work focusing on trees, this group of 12 photographs features trees falling while being logged on one magical morning. Shot with an 8×10 view camera under demanding technical and physical conditions, these images capture the beauty of the forest and the grace and power of a tree in motion. It’s a haunting peek into a dangerous world that few ever experience — a world of rough men and “widow makers.”

Bayles, who considers himself a committed environmentalist (“In a forest I see communities of beings, creating and collaborating in the rich cycle of living and dying,” he says), speaks at the gallery at 5 p.m. April 18, and it could be well worth a visit.

The gallery is also featuring some hand-made, collage style books by Linda Welch that look bright enough to infuse a little happiness into a day dampened by the drizzle of the dismal science.

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected:

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected:  On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian,

On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian,

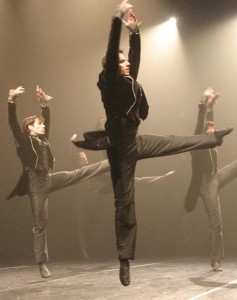

Neil Simon, American comedian: Also from Monday’s Oregonian (the full review ran online; a shortened version ran in print) is

Neil Simon, American comedian: Also from Monday’s Oregonian (the full review ran online; a shortened version ran in print) is

After the dust settles, the tsunami recedes or the cookie crumbles, depending on your metaphor of choice for our present economic condition, who will be left standing? More specifically, what regions of the country can expect to rebound quickly and which ones are headed for even deeper trouble?

After the dust settles, the tsunami recedes or the cookie crumbles, depending on your metaphor of choice for our present economic condition, who will be left standing? More specifically, what regions of the country can expect to rebound quickly and which ones are headed for even deeper trouble?

Surrealism and Ernst are the Collection’s core. The de Menils met Max Ernst (1891-1976) in Europe before World War II and became unalterably infected with his Surrealist vision. The show included a new film about the installation of a 1973 Ernst exhibit at nearby Rice University, supervised by Dominique de Menil. The film, “Max Ernst Hanging,†was produced by Francois de Menil and John de Menil, son and grandson of the de Menils, and features vintage black and white footage of Dominique de Menil organizing the show, as well as incredible coverage of Ernst, then in his early eighties, walking through the space while the exhibit is being hung, looking at pieces he hadn’t seen in years, and then mingling with Houston’s art patrons during the opening. Many of the pieces in the 1973 exhibit were on view in the current show. (

Surrealism and Ernst are the Collection’s core. The de Menils met Max Ernst (1891-1976) in Europe before World War II and became unalterably infected with his Surrealist vision. The show included a new film about the installation of a 1973 Ernst exhibit at nearby Rice University, supervised by Dominique de Menil. The film, “Max Ernst Hanging,†was produced by Francois de Menil and John de Menil, son and grandson of the de Menils, and features vintage black and white footage of Dominique de Menil organizing the show, as well as incredible coverage of Ernst, then in his early eighties, walking through the space while the exhibit is being hung, looking at pieces he hadn’t seen in years, and then mingling with Houston’s art patrons during the opening. Many of the pieces in the 1973 exhibit were on view in the current show. (

This time out Coburn’s tackling the omnibus economic bailout plan — surely a target for some tough critical thinking: How many Dutch boys with their fingers in the dike does it take to keep the thing from bursting, anyway? Unfortunately, it’s not just Coburn’s finger that’s all wet. His Amendment No. 175 to the economic stimulus bill is tough, and it’s critical. But it’s utterly lacking in thinking.

This time out Coburn’s tackling the omnibus economic bailout plan — surely a target for some tough critical thinking: How many Dutch boys with their fingers in the dike does it take to keep the thing from bursting, anyway? Unfortunately, it’s not just Coburn’s finger that’s all wet. His Amendment No. 175 to the economic stimulus bill is tough, and it’s critical. But it’s utterly lacking in thinking. OK, this one’s a little long, but it tries to get at some important issues of how we organize ourselves, operate in the world, through the lens of two “artist managers,” Seattle’s Anne Focke and the late Joel Weinstein.

OK, this one’s a little long, but it tries to get at some important issues of how we organize ourselves, operate in the world, through the lens of two “artist managers,” Seattle’s Anne Focke and the late Joel Weinstein. Things have been busy here at Scatter Central the last few days; so busy that we haven’t had a chance to post since we left poor

Things have been busy here at Scatter Central the last few days; so busy that we haven’t had a chance to post since we left poor Over at his alternate-universe home,

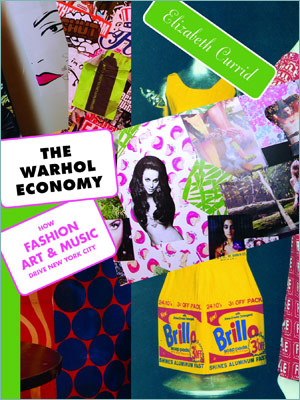

Over at his alternate-universe home,  Meanwhile, who’d have guessed that the path to understanding

Meanwhile, who’d have guessed that the path to understanding