By Bob Hicks

Charlotte Salomon was a Jewish girl who had the fortune to grow up amid a well-to-do creative family, the misfortune of growing up in a family that seemed to thrive on a certain amount of emotional drama, and the utter disaster of being born in Germany in 1917, which placed her smack in the middle of the rise of Nazism.

Her life, like so many others, ended in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, where she died in 1943, at age 26. But in a few fevered final months of 1941 and ’42, before she was shipped off from her refuge in southern France to the concentration camp, she left her mark on the world — a mark that, remarkably, survived, even though Charlotte did not. In those months the young artist created a portfolio of more than 700 paintings, many also covered with words or musical notations, that together amounted to an autobiography.

Her life, like so many others, ended in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, where she died in 1943, at age 26. But in a few fevered final months of 1941 and ’42, before she was shipped off from her refuge in southern France to the concentration camp, she left her mark on the world — a mark that, remarkably, survived, even though Charlotte did not. In those months the young artist created a portfolio of more than 700 paintings, many also covered with words or musical notations, that together amounted to an autobiography.

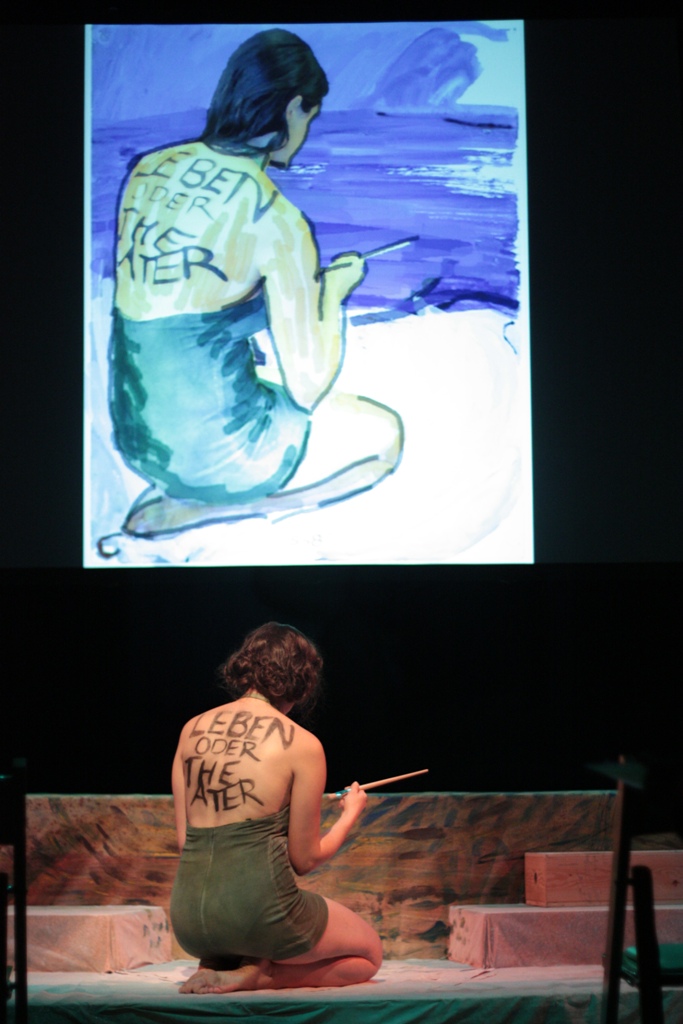

Director Sacha Reich has adapted Salomon’s story to the stage in the play Charlotte Salomon’s Life? or Theater?, which is running through Feb. 20 at Disjecta in a production by the Jewish Theatre Collaborative. It’s a fascinating story, told in an expressionistic self-conscious style that seems to echo Salomon’s approach to her own art. I reviewed it in Monday morning’s Oregonian, where it ran in a brief version. You can read the longer Oregon Live online version here.

Charlotte’s remarkable life’s work survives at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam, and you can see examples of her painting online here. Her story is one more reminder, if we needed one in our ethnically and religiously riven world, of the insanity of human culture, and one more reminder of the hope of the human spirit that thrives in spite of it.

*

Jamie M. Rea as Charlotte Salomon in “Life? or Theater?” Photo courtesy Jewish Theatre Collaborative.

The review stands pretty much on its own, as an overview of what is an overview exhibition. Each of the exhibit’s six areas of concentration makes up its own statement, and each could have been reviewed rigorously on its own, but for most viewers — and for the museum itself — the larger picture is more important.

The review stands pretty much on its own, as an overview of what is an overview exhibition. Each of the exhibit’s six areas of concentration makes up its own statement, and each could have been reviewed rigorously on its own, but for most viewers — and for the museum itself — the larger picture is more important.

This morning’s

This morning’s

In the latest turn in the

In the latest turn in the

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

Both were figurative artists, although in very different ways and with very different outlooks and techniques. Oliveira, who is represented in Portland by

Both were figurative artists, although in very different ways and with very different outlooks and techniques. Oliveira, who is represented in Portland by