Nobody knows her Marzipans from her Sugarplum Fairies as well as Martha Ullman West, the distinguished dance writer and charter member of Friends of Art Scatter. We here at Scatter Central are pleased as holiday punch — and with the right additives, that’s pretty darned pleased — to turn our space over to her for some insights into Oregon Ballet Theatre’s “The Nutcracker” and the long line of Nutcrackers leading up to it. Read on!

When George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker premiered at New York City Center in 1954, critic Edwin Denby reported that a “troubled New York poet sighed, “I could see it every day, it’s so deliciously boring.” I thought of that remark while viewing the same choreography, excellently danced, when Oregon Ballet Theatre opened its current run on Friday. I think the poet, not named by Denby, but possibly W.H. Auden, must have made his backhanded comment at intermission, following the first act party scene. I don’t know if he ever went back, but I have, again and again, in many versions, including a Nutcracker God-help-me on ice, and the boredom becomes less delicious each time.

When George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker premiered at New York City Center in 1954, critic Edwin Denby reported that a “troubled New York poet sighed, “I could see it every day, it’s so deliciously boring.” I thought of that remark while viewing the same choreography, excellently danced, when Oregon Ballet Theatre opened its current run on Friday. I think the poet, not named by Denby, but possibly W.H. Auden, must have made his backhanded comment at intermission, following the first act party scene. I don’t know if he ever went back, but I have, again and again, in many versions, including a Nutcracker God-help-me on ice, and the boredom becomes less delicious each time.

So on Friday, my mind wandered a bit — well, more than a bit — during that family party, notwithstanding adorable children in their party clothes, naughty Fritz and dancing dolls, all of whom performed just as they should have, harking back to the ghosts of Nutcrackers past — specifically James Canfield’s at OBT and Todd Bolender’s, which is still being performed by Kansas City Ballet. Both Canfield and Bolender (who danced in Balanchine’s 1954 production) have enlivened the party considerably, the former with mechanical dolls that are somewhat reminiscent of Dorothy’s companions in the Wizard of Oz (and they accompany Marie on her journey, in Canfield’s case to the palace of the Czar) and the latter with hordes of small boys galloping around the staid gathering tooting toy trumpets, and less formal social dances than Balanchine’s.

Nevertheless, there are elements of Balanchine’s party that I love and look for, particularly the Grandfather dance, which begins in stately decorum and concludes with a lively little pas de deux by the Grandmother and Uncle Drosselmeier, here performed by apprentice Ashley Smith and principal dancer Artur Sultanov, who will be seen in later performances as the Sugar Plum Fairy’s Cavalier. Moreover, his Marie is performed by a little girl and not an adult dancer pretending to be one. Julia Rose Winett, who danced the role on Friday night, has a jump that makes you think she has springs in her slippers. She can act, too. You know she’s scared to death during the battle of the mice and toy soldiers, even though the Mouse King really doesn’t look very frightening.

Nevertheless, there are elements of Balanchine’s party that I love and look for, particularly the Grandfather dance, which begins in stately decorum and concludes with a lively little pas de deux by the Grandmother and Uncle Drosselmeier, here performed by apprentice Ashley Smith and principal dancer Artur Sultanov, who will be seen in later performances as the Sugar Plum Fairy’s Cavalier. Moreover, his Marie is performed by a little girl and not an adult dancer pretending to be one. Julia Rose Winett, who danced the role on Friday night, has a jump that makes you think she has springs in her slippers. She can act, too. You know she’s scared to death during the battle of the mice and toy soldiers, even though the Mouse King really doesn’t look very frightening.

Which leads me to the reason that people like me, ballet aficionados by inclination as well as profession, attend multiple performances of a work whose score, as brilliant as it is, is entirely too familiar — and which, in the case of OBT’s current production, has a second-act set that at best looks like Laura Ashley on an acid trip and at worst like a bedspread in a Motel 6. Denby called The Nutcracker a pantomime; some call it a spectacle. Really, it’s a chance for dancers, children and professionals alike, to strut their stuff in performance. It’s particularly valuable for small companies that have few opportunities to perform — a long Nutcracker run gives company members at every level an opportunity to dance multiple roles and add detail, nuance and polish to their performances, a little like the actors at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. Sultanov, who has Russian training in character dance, was a truly splendid Drosselmeier, alternately stern and charming, sneaking back into Marie’s living room to make the broken nutcracker whole, and send Marie on her journey to the Palace of the Kingdom of the Sweets, her bed skittering around the stage.

There’s a story about that: Janet Reed, who danced Sugarplum in a suite of Nutcracker dances in Portland in 1934, and 20 years later originated the role of the Marzipan Sheperdess-in-Chief in New York, was ballet mistress when NYCB toured Nutcracker to Los Angeles. She brought her 12-year-old son with her. He got tapped to get under the bed and move it, and was given his musical cue repeatedly in rehearsal. Nevertheless, he missed it, and the bed didn’t budge until he heard his mother hiss from the wings, “Move, goddamit, move the goddam bed.”

The second act contains the technical demands, although the dance of the snowflakes that concludes the first exemplifies Balanchine’s rapidly changing floor patterns, performed on a stage slippery with fake snow. Balanchine made the corps important as no previous classical choreographer had, and OBT’s dancers were fleet and joyous, looking a lot like the big soft snowflakes that fell early in the day on Sunday. Canfied’s Snow was very different, alluding to several Petipa ballets including Swan Lake, with the corps sinking to the ground looking like sleeping birds, and containing a pas de deux for a Snow King and Queen. I like them both, and the backdrop and costumes in this production are more acceptable than elsewhere.

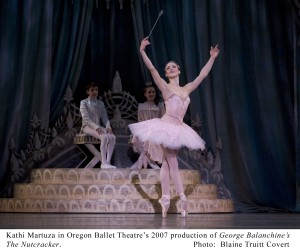

And so we come to the Sugarplum Fairy, the dance of the little angels, and the national dances that entertain Marie and her Nutcracker Prince. I loathe the wigs those darling little angels have to wear, but watched them anyway, and realized that in this choreography, which requires little tiny steps that make the cherubs look as if they’re on wheels, Balanchine has possibly borrowed from Georgian folk dance. As Sugarplum, Yuka Iino, who’s been dancing the role for several years, danced magically, with a new expansiveness and warmth in her solo variation. In the Grand Pas de Deux, partnered by newcomer Chauncey Parsons, whose training at the Kirov Academy in Washington D.C. is needless to say traditional and Russian, Iino’s balance was phenomenal, the musicality of her phrasing I daresay exactly what Balanchine had in mind. Parsons’ partnering was courtly, his variation danced with the natural ease we associate with Balanchine style.

In the national divertissements, Anne Mueller, like Reed known for her timing and wit, led the shepherdesses with just those qualities Friday night. She’s been known to do a terrific Dewdrop, the solo role in the Waltz of the Flowers and technically the most difficult in the ballet. Balanchine created it for Tanaquil LeClercq and it calls for fast, precise technique, the intricacy of the choreography turning the dancer’s feet into a lacemaker’s shuttle. Soloist Candace Bouchard danced it opening night with considerable finesse. Spanish (aka hot chocolate) is the first of the diverts, and I generally find it tedious; Adrian Fry however added some badly needed fire, a neat trick in a beige costume. In fact, except for Arabian and Chinese, the second act costumes are incredibly and relentlessly pink, which makes that backdrop look even more lurid.

All in all, OBT is dancing Nutcracker better every year. Which makes it worth seeing repeatedly. The company desperately needs new sets and costumes, however — for me, still longing for Campbell Baird’s beautiful “Russian” version made for a libretto that is set in Imperial Russia, this production actually is a distraction from the dancing, and that’s not good. Christopher Stowell, OBT’s artistic director, wants to mount a new production in honor of OBT’s 20th anniversary season next year; let’s hope the Board and the development office can pull that off. I’d rather not have next year’s Nutcracker haunted again by the ghosts of Nutcrackers past.