By LAURA GRIMES

Today my current first husband and I can legally drink. We’ve been married 21 years.

We can’t legally drink and celebrate together because I’m spending our special day with my mom. But it’s not the special days that make a marriage special. It’s the everyday little things. Like laughing and teasing. Like coffee together in the morning.

The first Christmas we spent together, my current first husband gave me a coffee maker. Sweet? I was pissed. But I gotta admit, that coffee maker was our loyal morning friend for 20 years, part of many a happy moment. Good memories are made of many a happy moment. Good marriages, too.

There’s one moment, though, that I will always hold dear.

***

My current first husband wrote a post recently and described a certain look in my eyes. Damn, but he beat me to it. Because little did he know that I have been working on a certain story that has just such a look, albeit a tad bit different and a shade bit farther … and on a certain somebody else. Actually, I’ve been tooling this story around in my head for many years. But a recent event swept through my brain like a tornado in Kansas and collected all the disparate thoughts, lifted them up, swirled them around and plunked them down again.

***

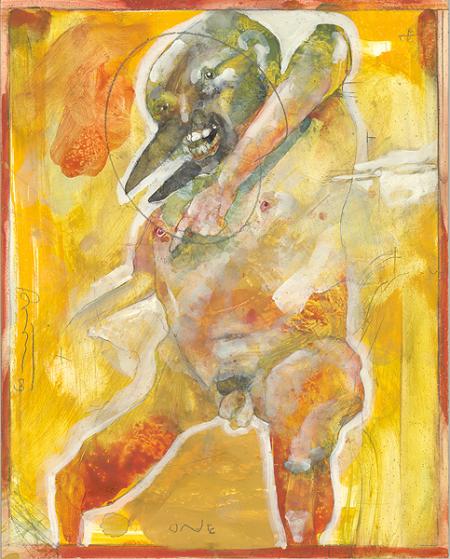

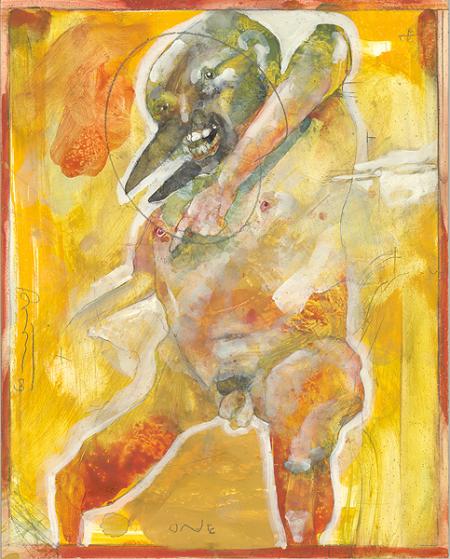

I met Rick Bartow a few weeks ago, and now I understand.

I understand a story I first started hearing years ago.

It was early 2002. Mr. Scatter and I and the large smelly boys – who were not so large and not so smelly back then – were driving several hours north to visit family. To visit my mom, in fact. The not-so-large not-so-smelly boys must have been blessedly quiet in the backseat for a long stretch of road. We’ll just chalk that up to divinity and not ask why.

It was early 2002. Mr. Scatter and I and the large smelly boys – who were not so large and not so smelly back then – were driving several hours north to visit family. To visit my mom, in fact. The not-so-large not-so-smelly boys must have been blessedly quiet in the backseat for a long stretch of road. We’ll just chalk that up to divinity and not ask why.

Mr. Scatter had recently visited Rick at his home and studio in Newport, Ore., for research to write a story. He had been typing away on it for a few days. But he was at loose ends. I could tell. Because he was talking about it incessantly, as much to figure out a throughway for the story as he was just plum excited.

He was trying to get his arms around a giant octopus and he hadn’t quite figured out how to land it.

***

After meeting Rick and seeing him perform, now I know why. Rick and two of his musician buddies did a show with Portland Taiko on July 2. Mr. Scatter is on the board of Portland Taiko, so even though I was looking forward to finally hearing Rick, I figured it would be an evening of smiling and shaking hands. I fretted about taking the right handbag.

It had been a blistering hot day and the event was taking place on the roof of the DeSoto Building in the Pearl, above Froelick Gallery. Frying came to mind. But by evening, the temperature had cooled to balmy, a slight breeze had kicked in and the sky was an uncanny even blue, deepening darker as the night wore on and lending a crisper backdrop for a half moon that lifted and slowly shifted through the show. It was magic.

Rick was even better. He was immediately open and generous, a magnetic guy who took a blues song and elevatored it down to deep dark basements faster than you can push a button. His songs were earthy and mystical and wrapped in rich, complex storytelling. He didn’t hold back.

What a gift. He talked of his past substance abuse, Vietnam, friends who have died, the beginnings of songs, the ends of songs. He wasn’t afraid of ugly. And he wasn’t afraid of sweet.

His stories unspooled for anyone lucky enough to have a seat. Friends. Strangers. He opened up for everyone. It was the gift he gave.

Afterward, Mr. Scatter and I chatted with him. I asked if he ever played at the Blues Festival, which was happening at the same time at Tom McCall Waterfront Park. He said no, he just can’t take the crowds. His nerves get to him.

I understand that, too. He seemingly wears all of his nerves on the outside. He takes in everything, absorbs it, feels it, and gives it back. For someone to perform like that, he must be perceptive to the slightest vibrations. And when you’re that sensitive, when all your pores are open to everything that comes in, crowds can be overwhelming. It’s too much all at once. There’s a lot of good in there, but the bad comes with it.

I want to say that Rick is a big man, but that doesn’t sound right. He’s a big spirit. At once gentle and rough.

Continue reading Scenes from a writers’ marriage: How he got that story →

Nobody seems to remember anymore what the fabled bull and bear stand for, the story comments, and they got that right: If investors and manipulators hadn’t conveniently forgot that the bull periodically and inevitably transforms into a bear, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now. Optimism is a lovely thing, but not when it doesn’t have its feet on the ground.

Nobody seems to remember anymore what the fabled bull and bear stand for, the story comments, and they got that right: If investors and manipulators hadn’t conveniently forgot that the bull periodically and inevitably transforms into a bear, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now. Optimism is a lovely thing, but not when it doesn’t have its feet on the ground.

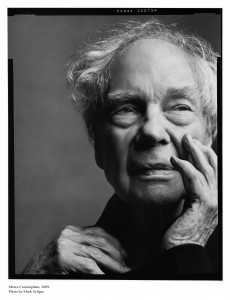

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche. Readers of Laura Grimes’ recent post

Readers of Laura Grimes’ recent post  About visual art, definitely. We’ve created a mumbo-jumbo priesthood of commentary and pretend the intellectual abstraction is more important than the physical experience of the art itself. Which it is, but only sometimes. And far less often than the priesthood likes to think.

About visual art, definitely. We’ve created a mumbo-jumbo priesthood of commentary and pretend the intellectual abstraction is more important than the physical experience of the art itself. Which it is, but only sometimes. And far less often than the priesthood likes to think.

It was early 2002. Mr. Scatter and I and the large smelly boys – who were not so large and not so smelly back then – were driving several hours north to visit family. To visit my mom, in fact. The not-so-large not-so-smelly boys must have been blessedly quiet in the backseat for a long stretch of road. We’ll just chalk that up to divinity and not ask why.

It was early 2002. Mr. Scatter and I and the large smelly boys – who were not so large and not so smelly back then – were driving several hours north to visit family. To visit my mom, in fact. The not-so-large not-so-smelly boys must have been blessedly quiet in the backseat for a long stretch of road. We’ll just chalk that up to divinity and not ask why. Today, in the throes of an infernal Pacific Northwest heat wave that has the thermometer rattling up toward 107, that red-baked head is on my mind again. Kind of blue, kind of hot, an oddly triumphal moan, mixed of resignation and endurance and somehow coming out on the sweet side of things: I ain‘t dead.

Today, in the throes of an infernal Pacific Northwest heat wave that has the thermometer rattling up toward 107, that red-baked head is on my mind again. Kind of blue, kind of hot, an oddly triumphal moan, mixed of resignation and endurance and somehow coming out on the sweet side of things: I ain‘t dead. Here in the Art Scatter sauna we wouldn’t stoop to

Here in the Art Scatter sauna we wouldn’t stoop to

Joe Meek, maybe. Jedediah Smith. Liver-Eating Johnson. Jim Bridger.

Joe Meek, maybe. Jedediah Smith. Liver-Eating Johnson. Jim Bridger.