Most of you know at least a little bit about Fertile Ground, Portland’s festival of new performance works, which has been playing on stages big and small around the city and continues to do so through Feb. 2. Marty Hughley and friends have covered a lot of the action, including Marty’s middle-of-the-action roundup, for The Oregonian. In its second year, the festival has expanded from its theater roots to include other sorts of performance, too, especially dance.

I’ve seen a bit of it, including White Bird’s premiere of dances by Tere Mathern and Minh Tran, and Polaris Dance Theatre’s iChange. Third Angle New Music Ensemble’s Hearing Voices wasn’t officially part of the festival but dovetailed nicely with it: Two of its four compositions were premieres, another had a fresh arrangement, and all four were story-pieces with narration — musical dramas.

On Sunday I saw The Hillsboro Story, Susan Banyas’s memory piece about a little-known but fascinating piece of American civil rights history that was not so long ago and not so far away, although life has barreled ahead so much in the past 55 years that for an astonishing number of Americans the civil rights years might as well be hung forgotten in the cloakroom alongside the colonial era’s three-corner hats.

For that reason alone — the short communal memory of a culture that consistently shortchanges its own past and often misinterprets it even when it does pay attention — The Hillsboro Story is worth telling, and seeing. I hope the play has a healthy future in schools and youth theaters — not that it isn’t a good piece of theater for adults (it is), but because still-developing hearts and minds in particular need to understand this vital part of their heritage.

Structurally, The Hillsboro Story is a little like The Laramie Project, the story of the Wyoming torture/murder of gay student Matthew Shepard and its aftermath. The difference is that Banyas, the teller of this tale, was there: She was a third-grader in the southern Ohio town of Hillsboro when, on the night of July 5, 1954, someone scattered gasoline around the ramshackle public elementary school in the black part of town and lit a match to it.

As it turns out, the firebug was Philip Partridge, the county engineer, who was fed up with fighting the town’s white power structure over school segregation and the rundown quality of the school for black kids. He figured, if the school burned down, the town would have to integrate its schools: After all, the Supreme Court had just ruled against school segregation in its landmark Brown v. Board of Education case.

There are heroes aplenty in this story besides Partridge, whose act of civil disobedience might well be branded terrorism today (the play doesn’t delve deeply into the ethical issues of this sort of protest; but then, Partridge acted at a time when black men were still being lynched in America and nobody much did anything about it).

None are more heroic than the group of African American mothers who pressed their case unceasingly against the town fathers who patted them on the back and assured them that something would be done “later.” Nor is any image in the show quite so startling as black performer LaVerne Green’s fervid delivery of Mississippi Senator James Eastland’s fervid, vile speech asserting the right of white Southerners to kill their black neighbors.

What makes The Hillsboro Story more than just another formulaic tale of triumph over adversity is that we see it consistently through the eyes of Banyas as a third-grader, only dimly aware of the titanic social struggle playing out around her. Banyas’s memory pieces have always been personal, and they’ve always been fractured: not straight narratives but interweavings of thought and reminiscence, small intimate moments insisting on their place alongside the big things.

That helps emphasize that this isn’t strictly a story of good guys versus bad guys, a tale that makes it easy to point a finger and say, “Weren’t they awful.” By inserting herself as an unformed observer, trying to figure out why her world is changing, Banyas puts us all in the center of the thing, and reminds us that things that seem crystal clear now could seem cloudy then. This is a story of a time when things were different, when people thought in different ways, when an entire culture was just beginning to take a deep look at itself and think about what words like “freedom” and “equality” truly mean.

The Hillsboro school battle was the first case in the North to test the teeth in Brown v. Board of Education. The Hillsboro school board thought it could slide through despite the court ruling and just do what it wanted. It was wrong. And if this story has been largely forgotten, it’s because Hillsboro pretty much preferred to keep it buried. Banyas’s determination to disinter the tale does the town an honor: She tells the story with grace, and humility, and understanding, and love.

With Banyas’s fine interwoven script, choreography and direction by Gregg Bielemeier, music by David Ornette Cherry and good performances by Green, Banyas, Paige Jones and Jennifer Lanier in multiple roles, The Hillsboro Story shows why Fertile Ground is such an exciting development for Portland. Good stories are out there, just waiting for a chance to be told.

*

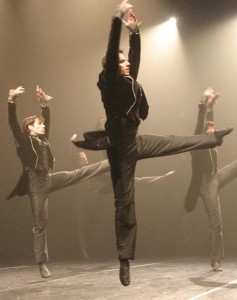

Pictured: LaVern Green, Paige Jones and Susan Banyas in “The Hillsboro Story.” Photo: Julie Keefe

“This score is my bible,”

“This score is my bible,”  Things have been busy here at Scatter Central the last few days; so busy that we haven’t had a chance to post since we left poor

Things have been busy here at Scatter Central the last few days; so busy that we haven’t had a chance to post since we left poor Over at his alternate-universe home,

Over at his alternate-universe home,  Meanwhile, who’d have guessed that the path to understanding

Meanwhile, who’d have guessed that the path to understanding