Chatting with a friend in the lobby of Keller Auditorium during halftime of Portland Opera’s Cosi fan tutte on Friday night, Mr. Scatter became aware of a controversy he hadn’t realized existed.

“Audiences tend to love this production,” my friend, an exceptionally knowledgeable follower of the opera world, sighed. “And critics tend to hate it.”

Up to this point I’d been having a rather jolly time myself, although I knew the production, which originated in 2003 at Santa Fe Opera and emphasizes brisk farcical shtick, wasn’t strictly traditional. So I stuck his comment in the back of my mind, returned to my seat for the second act, and continued to have a jolly time along with the rest of the audience, right up to the curtain call.

And this morning I did a little researching. It’s true. A lot of critics (though by no means all) have found this Cosi distressingly populist. “A gag-filled, vulgar romp,” J.A. Van Sant wrote in Opera Today, reviewing Santa Fe’s 2007 revival. That might sound like a good ad quote, but he didn’t mean it as a compliment.

Since Van Sant seems to speak for a lot of other critics, let’s give him a little more room to explain himself:

Politely put, (stage director James) Robinson’s Cosi was a gag-filled, vulgar romp. Such is not Mozart’s Cosi, an elegant, ironic comedy – not an ambiguous study of human nature requiring Regietheatre treatment, as is the present day style with this piece. To make Cosi into slapstick comedy combined with faux psychological exploration of the characters is to miss the point.

Essentially a bittersweet comedy of character types, set to some of Mozart’s most exhilarating and beautiful music, Cosi indeed has dark edges that serve to heighten amusement over the foibles of human nature.

You shouldn’t overdo the darkness, Van Sant continued, but you shouldn’t sacrifice the elegance to showy gimmicks, either.

A couple of other points emerged from other critics.

- First, the not-too-reluctantly philandering sisters in this play (the story is by Lorenzo da Ponte, who also wrote the librettos for Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and Don Giovanni) and their gentleman-and-an-officer lovers have traditionally been played by older singers, suggesting that these erotic foibles are less the result of sheer youthful exuberance and more of something innate in human nature.

- Second, the play is very much about social convention at a level of society in which adherence to social convention is extremely important. These characters, if they’re going to sin, would do so cautiously, with a sense of decorum, not with casual friskiness. To give Cosi the sheen of 1950s naughtiness that this production does is historically misleading and saps some of the intellectual vigor from an opera that has a far subtler soul.

Objections noted. And on this one, I’m going to side with the audience.

Continue reading This ‘Cosi’ is a farce. You got a problem with that?

10:10 p.m., this joint is emptying out.

10:10 p.m., this joint is emptying out.

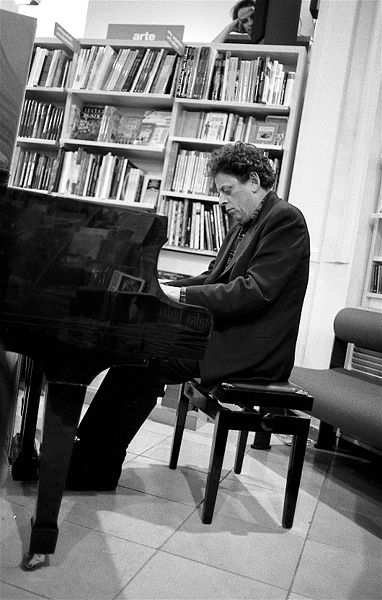

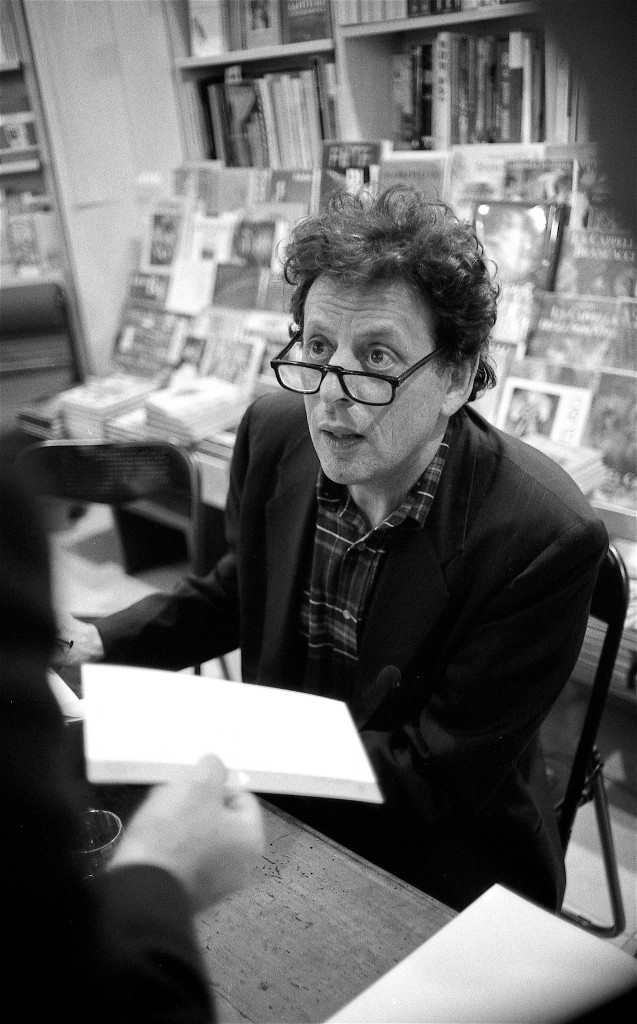

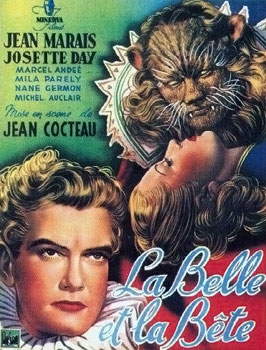

6:14 p.m. Friday, Nov. 6, Keller Auditorium, in the lobby: One hour and 16 minutes to showtime, the show being the West Coast premiere of Philip Glass’s Orphee, by Portland Opera.

6:14 p.m. Friday, Nov. 6, Keller Auditorium, in the lobby: One hour and 16 minutes to showtime, the show being the West Coast premiere of Philip Glass’s Orphee, by Portland Opera.

What this means is that, while you’re filing into Keller Auditorium before the show, I’ll be in the lobby seated at a table with several other bloggers, dashing out immediate impressions and committing them to cyberspace before I have time to repent and delete. I’ll have a backstage tour beforehand, and yes, I do get to see the show, after which I’ll dash back to my laptop and blog some more. This will be either the rough draft of history or outtakes of an unsifted mind, but I will Not. Look. Back.

What this means is that, while you’re filing into Keller Auditorium before the show, I’ll be in the lobby seated at a table with several other bloggers, dashing out immediate impressions and committing them to cyberspace before I have time to repent and delete. I’ll have a backstage tour beforehand, and yes, I do get to see the show, after which I’ll dash back to my laptop and blog some more. This will be either the rough draft of history or outtakes of an unsifted mind, but I will Not. Look. Back. So when Susan asked whether I’d be a guest performer in Well Arts’ fall show, Voices of Our Elders, I said yes. The process is fascinating. Well Arts people do a 10-week workshop on memoir and creative writing with older people in care centers, listening to their stories, transcribing them, helping them shape them. The result is a show of monologues and a few dialogues from people looking back on their lives, on what was important, and contemplating what’s to come. It’s a fundamental form of personal history and an emotionally involving form of documentary theater.

So when Susan asked whether I’d be a guest performer in Well Arts’ fall show, Voices of Our Elders, I said yes. The process is fascinating. Well Arts people do a 10-week workshop on memoir and creative writing with older people in care centers, listening to their stories, transcribing them, helping them shape them. The result is a show of monologues and a few dialogues from people looking back on their lives, on what was important, and contemplating what’s to come. It’s a fundamental form of personal history and an emotionally involving form of documentary theater.