By Bob Hicks

Twenty-six years after she first impersonated the fabulous Sophie Tucker onstage, the big-talented Portland singer and comedian Wendy Westerwelle’s return to Soph: An Evening with the Last of the Red-Hot Mamas is a revival in more than one way. It marks Westerwelle’s own continuing return to the spotlight following her bravura turn earlier this year in Martin Sherman‘s one-woman play Rose (which I wrote about here and here) as well as a revival of interest in Tucker, a giant of 20th century American entertainment who has been lamentably overlooked in the years since her death in 1966. (She was born in 1886 in the Ukraine but arrived soon after in Hartford, Connecticut, where her family went into the restaurant business and young Sophie began singing for tips.)

You can catch up with my review of Soph for The Oregonian here, then stick around for a ramble through the pop-history parade. Westerwelle’s performance has got me to thinking about yet another revival of sorts, a historical reminder of the changing cavalcade of American popular culture and the important if sometimes embarrassing spectacle of facing up to what we’ve been as a nation and what it means to what we are now.

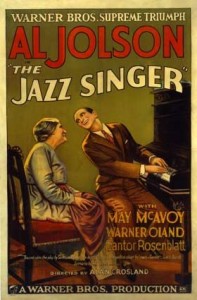

Soph is primarily a celebration of Tucker’s bawdy wit and rollicking style; Westerwelle isn’t looking to uncover any demons or wag her finger at the occasional ruthlessness that Tucker employed in pursuit of her career. But to Westerwelle’s credit, and to the credit of director Don Horn, who had a big hand in reshaping the script, neither does she shy from a few uncomfortable facts, such as Tucker’s vaudeville beginnings performing “coon songs” in blackface. It was a standard format in vaudeville, the grinning minstrelsy and exaggerated drawls of the happy watermelon-loving “colored folk” as performed by white (and sometimes black) entertainers.

Soph is primarily a celebration of Tucker’s bawdy wit and rollicking style; Westerwelle isn’t looking to uncover any demons or wag her finger at the occasional ruthlessness that Tucker employed in pursuit of her career. But to Westerwelle’s credit, and to the credit of director Don Horn, who had a big hand in reshaping the script, neither does she shy from a few uncomfortable facts, such as Tucker’s vaudeville beginnings performing “coon songs” in blackface. It was a standard format in vaudeville, the grinning minstrelsy and exaggerated drawls of the happy watermelon-loving “colored folk” as performed by white (and sometimes black) entertainers.

In the latest turn in the

In the latest turn in the  “If I can’t sell it gonna keep sittin’ on it, never gonna give it away,” the hard-bitten narrator of the bawdy blues tune Keep on Truckin’ declares. Her hardcore-capitalist sentiment is definitely not the motto at Art Scatter, where we tend to write what we write just because it sends little shivers up and down our spines. Still, we have an abiding fondness for those stalwarts of the heritage media who help us keep the spring in our mattress by paying cash on the barrel head for written contributions. O admirable concept! Here are a few recent pieces wherein we’ve made the noble trade of play for pay. We thank the editors of The Oregonian for assigning these exercises in fundamental free trade, and the publisher for his largesse:

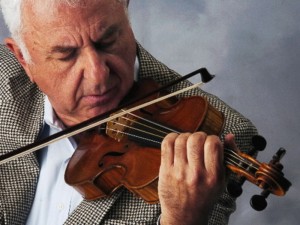

“If I can’t sell it gonna keep sittin’ on it, never gonna give it away,” the hard-bitten narrator of the bawdy blues tune Keep on Truckin’ declares. Her hardcore-capitalist sentiment is definitely not the motto at Art Scatter, where we tend to write what we write just because it sends little shivers up and down our spines. Still, we have an abiding fondness for those stalwarts of the heritage media who help us keep the spring in our mattress by paying cash on the barrel head for written contributions. O admirable concept! Here are a few recent pieces wherein we’ve made the noble trade of play for pay. We thank the editors of The Oregonian for assigning these exercises in fundamental free trade, and the publisher for his largesse: I remember him beaming above the breakwaters at Cascade Head on the Oregon Coast, a glass of good wine in one hand and the other sweeping through space in accompaniment to a robust story.

I remember him beaming above the breakwaters at Cascade Head on the Oregon Coast, a glass of good wine in one hand and the other sweeping through space in accompaniment to a robust story.

You still occasionally hear people refer to it as Morris’s winking bad-boy spoof of the ubiquitous holiday story ballet, but people who think that about it (a) aren’t paying a lot of attention to the dance itself, and (b) apparently haven’t read the

You still occasionally hear people refer to it as Morris’s winking bad-boy spoof of the ubiquitous holiday story ballet, but people who think that about it (a) aren’t paying a lot of attention to the dance itself, and (b) apparently haven’t read the

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

Both were figurative artists, although in very different ways and with very different outlooks and techniques. Oliveira, who is represented in Portland by

Both were figurative artists, although in very different ways and with very different outlooks and techniques. Oliveira, who is represented in Portland by  He shouldn’t have been, of course. After all, Deemer knows this stuff. He teaches screenwriting at Portland State University, and is a terrific playwright, and a pioneer in the expanded-universe form of hyperdrama, and he’d already done another ultra-low-budget film, Deconstructing Sally, which we wrote about a little over a year ago

He shouldn’t have been, of course. After all, Deemer knows this stuff. He teaches screenwriting at Portland State University, and is a terrific playwright, and a pioneer in the expanded-universe form of hyperdrama, and he’d already done another ultra-low-budget film, Deconstructing Sally, which we wrote about a little over a year ago

It was the thirtieth anniversary of Mule Days, and Mr. Scatter, who was on the spot for last year’s festivities, which he wrote about

It was the thirtieth anniversary of Mule Days, and Mr. Scatter, who was on the spot for last year’s festivities, which he wrote about  Then she took a batch of her rewritten stories, entered them into a prestigious professional competition, and strutted off with a passel of awards. That experience has made Mr. Scatter deeply suspicious of awards ever since. It also played a crucial role in the briefness of his own tenure at that particular less-than-august journal of news and opinion, a place that greeted him on his first day of work with a single rule, banning in-house sexual fraternization: Don’t dip your pen in the company ink. That the prize-winning “writer” was regularly inking and dipping with the publication’s owner did not help Mr. Scatter’s position, although it seemed to do wonders for her own.

Then she took a batch of her rewritten stories, entered them into a prestigious professional competition, and strutted off with a passel of awards. That experience has made Mr. Scatter deeply suspicious of awards ever since. It also played a crucial role in the briefness of his own tenure at that particular less-than-august journal of news and opinion, a place that greeted him on his first day of work with a single rule, banning in-house sexual fraternization: Don’t dip your pen in the company ink. That the prize-winning “writer” was regularly inking and dipping with the publication’s owner did not help Mr. Scatter’s position, although it seemed to do wonders for her own.