Martha Ullman West, Art Scatter’s chief international dance correspondent, took in “La Danse,” Frederick Wiseman’s documentary film about the legendary Paris Opera Ballet. How does it go wrong? Let her count the ways:

Last night I took a friend to Cinema 21 to see a benefit screening of La Danse, documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman’s take on the Paris Opera Ballet. Before I scatter a little venom about this highly uneven film, I would like to express my profound gratitude to Cinema 21 for supporting Oregon Ballet Theatre, the beneficiary of the screening.

Wiseman likes to be a fly on the wall with a camera (conjuring interesting visions of Vincent Price, come to think of it) at various kinds of institutions, from high schools to juvenile courts. And he’s no stranger to ballet: In 1993 he did a similar film on American Ballet Theatre, Ballet.

That one was OK, but just OK, though I quite loved the scene of then artistic director Jane Hermann losing her temper on the phone with the Lincoln Center administration, using language she did not learn at tea in the James Room at Barnard College.

That one was OK, but just OK, though I quite loved the scene of then artistic director Jane Hermann losing her temper on the phone with the Lincoln Center administration, using language she did not learn at tea in the James Room at Barnard College.

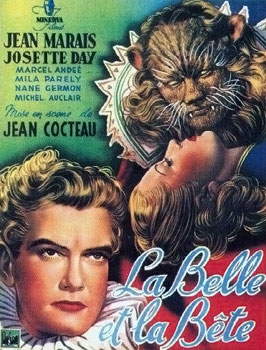

La Danse isn’t quite the worst dance film I’ve ever seen — Robert Altman’s The Company, not quite a documentary but not quite a feature film either, is probably worse.

But what these two directors seem to me to share is really lousy taste in choreography.

In The Company, which is about the Joffrey Ballet, all the revelations of the inner workings of the company culminate in a performance of the ghastly The Blue Snake, choreographed by Robert Desrosiers.

In La Danse, we see a lot of rehearsals and a pretty lengthy slice of performance of Angelin Preljocaj’s Medea, which culminates in the murder of her two children and the gorgeous ballerina Delphine Moussin covered in fake blood. There are literally buckets of the stuff on the stage, and post-infanticide, she carries a large piece of red fabric in her mouth.

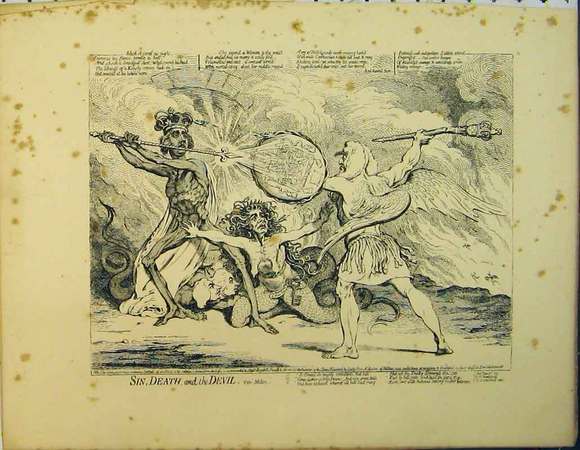

Scatterers who are familiar with Martha Graham’s Cave of the Heart, which has no fake blood on a stage defined by Isamu Noguchi’s extraordinary set pieces and props, surely will feel as outraged as I was by this cheap knock-off.

In Graham’s masterpiece, Medea seems to pull out her own guts, which are represented by a red velvet rope: It’s a brilliant piece of theater that makes me shudder every time I see it. Preljocaj’s buckets of blood would have given me the giggles if I hadn’t remembered Melina Mercouri laughing her way through a performance of Medea in Jules Dassin’s movie Never On Sunday.

The rehearsals recorded in La Danse are quite interesting, especially when Preljocaj, having set the ballet, tells Moussin that it is now up to her, giving her a good deal of freedom to interpret the role.

Moussin is hardly the only perfectly gorgeous dancer we see in the film. All the dancers he films are lovely to look at, with extraordinary technique, and he shows them working in studios with raked floors, high up in the Palais Garnier, the arched windows overlooking the Paris rooftops. (Those shots, as well as exterior shots from the roof of the building, made me want to jump on the next plane to Paris).

We see them taking a break, eating in their own cafeteria (in which the food looks neither healthy nor like haute cuisine), getting on the elevator, walking down long corridors, being made up.

We also see them being coached by long-retired dancers, in one session a man and a woman (unidentified; typical Wiseman) arguing with each other about whether a leg should be raised or lowered. It’s all very amusing and quite lovable, like the old dancers in that most excellent of ballet films, Ballets Russes, by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

We also see them being coached by long-retired dancers, in one session a man and a woman (unidentified; typical Wiseman) arguing with each other about whether a leg should be raised or lowered. It’s all very amusing and quite lovable, like the old dancers in that most excellent of ballet films, Ballets Russes, by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

But that seems to be Wiseman’s only real bow to tradition. He completely omits the Paris Opera Ballet School, which is where those poor murdered children in Medea, forced to huddle with buckets over their heads, came from. For a good look at the ethos of the Paris Opera Ballet, and how students rise from the ranks, through a fixed hierarchy, there is an old, black-and-white French film called in English Ballerina that tells you a lot more about it than La Danse.

In a piece of directorial self-indulgence that makes this 158-minute film much, much too long, you do become extremely familiar with the corridors of the upper floors and the subterranean passages of the Palais Garnier. I did quite like the fish who, in the words of a colleague, had set up housekeeping in a flooded passage, and the metaphor of the beekeeper on the roof of the building was not lost on me: With providers of food, costumiers, set builders, accompanists, janitors, cleaners, ballet masters and Brigitte LeFevre, the queen bee who is the artistic director of the company, the building is indeed a hive of activity.

And it was a pleasure, a profound pleasure, to see these dancers performing some bits of Paquita in the grand tradition — and what a contrast to the rehearsals of Rudolf Nureyev’s unspeakable staging of The Nutcracker, which would appear to be completely free of children.

Wiseman does know how to film dancers: He isn’t obsessed with their feet, and he does show the whole body. On the other hand, a lot of the time, in the studio, he filmed them from the back so we saw their reflections in the mirrors — somewhat distorted, at that.

In the end, La Danse provides a pretty distorted view of a company that is one of the best in the world, and that’s a pity. It deserves better, and so do we.

At his perch on the news desk, Charlie was known to lightly mock certain passages of flowery writing as he slashed through copy with his big black pencil. Sometimes he’d sigh or giggle and choose to overlook a phrase that not so privately drove him crazy: He knew which writers had permission to roam and which did not. But that didn’t stop him from pulling out his inkpad and his favorite stamp and branding the hard copy with his own gleeful judgment. The type was in a florid, immediately post-Gutenberg, barely readable old gothic. “WRETCHED EXCESS,” it said.

At his perch on the news desk, Charlie was known to lightly mock certain passages of flowery writing as he slashed through copy with his big black pencil. Sometimes he’d sigh or giggle and choose to overlook a phrase that not so privately drove him crazy: He knew which writers had permission to roam and which did not. But that didn’t stop him from pulling out his inkpad and his favorite stamp and branding the hard copy with his own gleeful judgment. The type was in a florid, immediately post-Gutenberg, barely readable old gothic. “WRETCHED EXCESS,” it said.

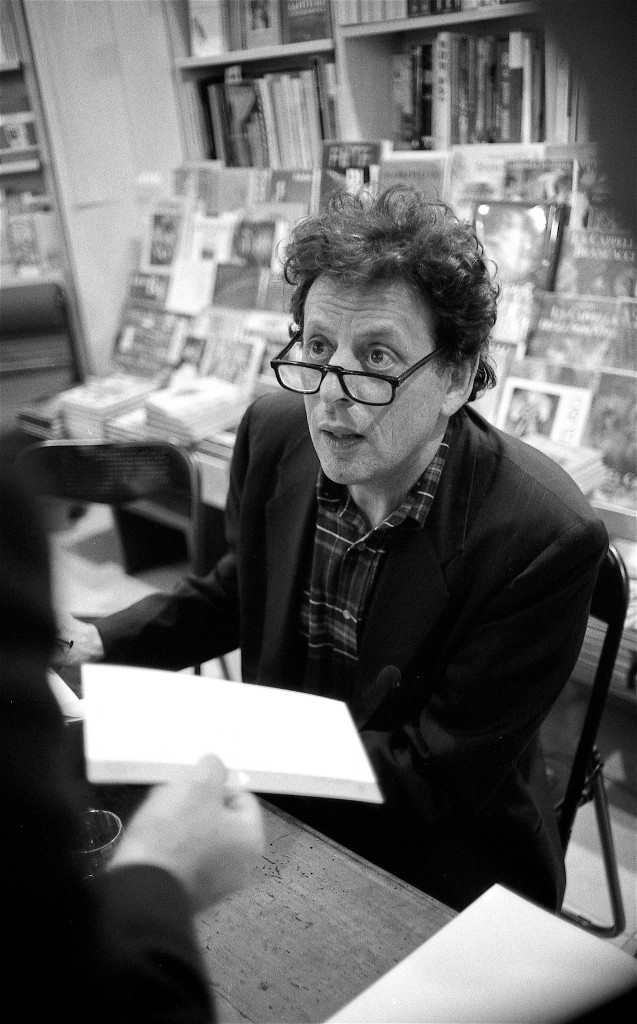

Then, at midday Friday, the Scatter duo showed up at the Gerding Theater in the Armory to see dancer Linda Austin and her cohort J.P. Jenkins tear up the joint with a fascinating visual, musical and movement response to Mark Applebaum‘s elegant series of notational panels, The Metaphysics of Notation, which has been ringing the mezzanine railings above the Gerding lobby for the past month. Every Friday at noon someone has been interpreting this extremely open-ended score, and this was the final exploration. California composer Applebaum will be one of the featured artists this Friday at the Hollywood Theatre in the latest concert by

Then, at midday Friday, the Scatter duo showed up at the Gerding Theater in the Armory to see dancer Linda Austin and her cohort J.P. Jenkins tear up the joint with a fascinating visual, musical and movement response to Mark Applebaum‘s elegant series of notational panels, The Metaphysics of Notation, which has been ringing the mezzanine railings above the Gerding lobby for the past month. Every Friday at noon someone has been interpreting this extremely open-ended score, and this was the final exploration. California composer Applebaum will be one of the featured artists this Friday at the Hollywood Theatre in the latest concert by

That one was OK, but just OK, though I quite loved the scene of then artistic director Jane Hermann losing her temper on the phone with the Lincoln Center administration, using language she did not learn at tea in the James Room at Barnard College.

That one was OK, but just OK, though I quite loved the scene of then artistic director Jane Hermann losing her temper on the phone with the Lincoln Center administration, using language she did not learn at tea in the James Room at Barnard College. We also see them being coached by long-retired dancers, in one session a man and a woman (unidentified; typical Wiseman) arguing with each other about whether a leg should be raised or lowered. It’s all very amusing and quite lovable, like the old dancers in that most excellent of ballet films, Ballets Russes, by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

We also see them being coached by long-retired dancers, in one session a man and a woman (unidentified; typical Wiseman) arguing with each other about whether a leg should be raised or lowered. It’s all very amusing and quite lovable, like the old dancers in that most excellent of ballet films, Ballets Russes, by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

10:10 p.m., this joint is emptying out.

10:10 p.m., this joint is emptying out.

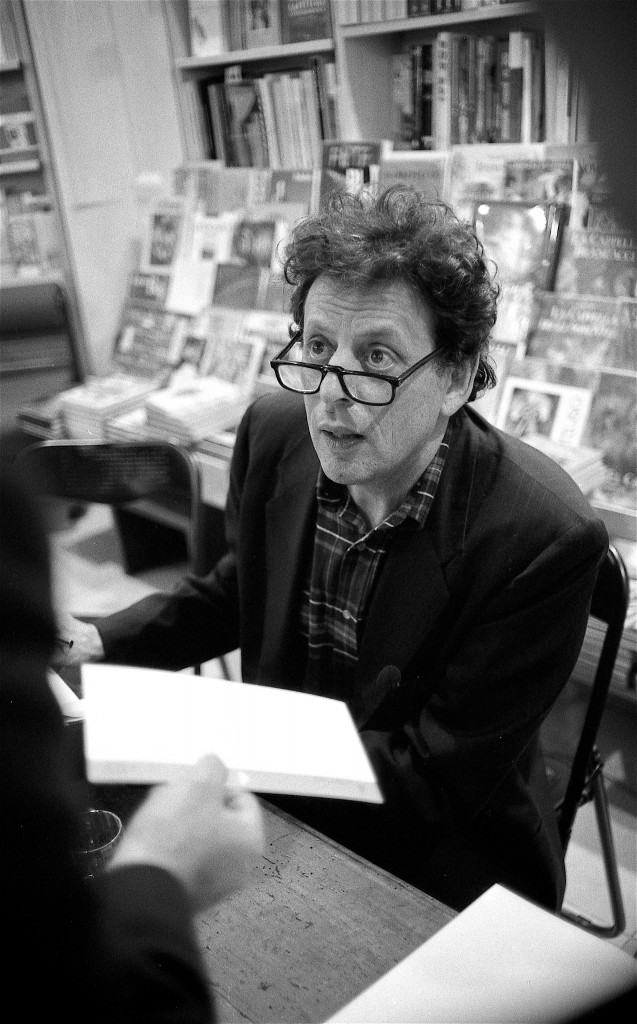

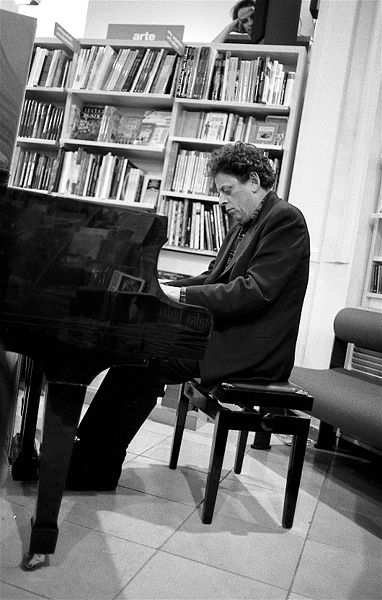

6:14 p.m. Friday, Nov. 6, Keller Auditorium, in the lobby: One hour and 16 minutes to showtime, the show being the West Coast premiere of Philip Glass’s Orphee, by Portland Opera.

6:14 p.m. Friday, Nov. 6, Keller Auditorium, in the lobby: One hour and 16 minutes to showtime, the show being the West Coast premiere of Philip Glass’s Orphee, by Portland Opera.