It’s a little after 3 on Sunday afternoon, and Mr. Scatter is wearing pants.

I mention this because apparently several people in Portland aren’t wearing pants at the moment, and what’s more, they’re riding around town on public transit.

I mention this because apparently several people in Portland aren’t wearing pants at the moment, and what’s more, they’re riding around town on public transit.

As Scatter friend Peter Ames Carlin reported in Saturday’s Oregonian, a carefully calculated event called the No Pants on Max Ride shed its inhibitions at 3 this afternoon, allowing “all local pranksters to let their freak flags, and boxers or bloomers, fly in public.”

Evidently those canny policy wonks at MAX, Portland’s light-rail system, have decided this is A-OK, as long as everyone follows the rules of decorum and keeps their privates private with suitable swaths of undergarment.

This could actually be an improvement on the cheeky low-rider revelations of some of the transit system’s sloppier regular customers. Still, Mr. Scatter detects a whiff of desperation in the whole knock-kneed enterprise. Surely this is a product of those KEEP PORTLAND WEIRD folks on the prowl again.

I’m all for weirdness, I suppose, but I wonder: Can it truly be weird if it feels compelled to announce itself? Shouldn’t weirdness simply … happen? If weirdness arrives with a press release, is it nothing but marketing?

A couple of points about No Pants on Max:

- First, it isn’t original. In its third year, it mimics a similar, older and much bigger trousers-free event on New York’s subway system. How weird is copycat weird?

- Second, Portland’s pants-free pioneers GOT PERMISSION. How anarchic can it be if you don’t doff your trousers until the authorities give you the green light? How can you twit the system when the system says it’s OK?

Imagine the No Pants scene in one of those recruits-and-a-drill-sergeant movies. (Mr. Scatter imagines a young Richard Gere as the rebel-with-a-permit-clause and Louis Gossett Jr. as the contemptuous sarge):

Sir! Permission to drop trou, sir!

Stand up straight, soldier! You’re a disgrace!

Yes, sir! Standing up straight, sir!

You disgust me, soldier. If I had my way dropping trou in public would never be tolerated. What if the enemy saw this display? But the politicians at the Pentagon say we have to put up with this sort of perversion in the New Army. Permission granted. But wait until I’ve turned my eyes away.

Thank you, sir! Sorry about your disgust, sir!

Dismissed, maggot.

All in all, Mr. Scatter prefers to keep his pants in place. But then, Mr. Scatter is also aware that he doesn’t possess the prettiest legs in town, and he feels a certain social responsibility to protect the visual sensibilities of his fellow citizens.

Yet everything about No Pants on Max appears to be legit. Too legit. Conspiracy theorists are wrong about this one: It’s definitely not part of a vast cover-up.

That would be just weird.

***************

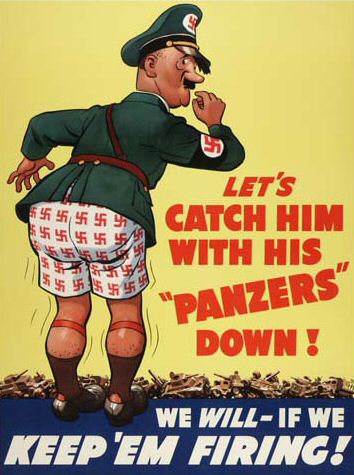

- ILLUSTRATION: World War II poster, United States Government Office. Collection Northwestern University Library. Wikimedia Commons.

As near as I can figure in the aftermath, I read about 75 books in 2009: a decent clip, though still pretty minor-league compared to the truly devoted. I won’t pretend to be as catholic or compulsive in my reading habits as Art Scatter’s friend

As near as I can figure in the aftermath, I read about 75 books in 2009: a decent clip, though still pretty minor-league compared to the truly devoted. I won’t pretend to be as catholic or compulsive in my reading habits as Art Scatter’s friend

Our good friend Barry Johnson, the original Scatterer, who had the idea for this blog and brought it into being before parting amicably to pursue his own arts column and

Our good friend Barry Johnson, the original Scatterer, who had the idea for this blog and brought it into being before parting amicably to pursue his own arts column and

That one was OK, but just OK, though I quite loved the scene of then artistic director Jane Hermann losing her temper on the phone with the Lincoln Center administration, using language she did not learn at tea in the James Room at Barnard College.

That one was OK, but just OK, though I quite loved the scene of then artistic director Jane Hermann losing her temper on the phone with the Lincoln Center administration, using language she did not learn at tea in the James Room at Barnard College. We also see them being coached by long-retired dancers, in one session a man and a woman (unidentified; typical Wiseman) arguing with each other about whether a leg should be raised or lowered. It’s all very amusing and quite lovable, like the old dancers in that most excellent of ballet films, Ballets Russes, by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

We also see them being coached by long-retired dancers, in one session a man and a woman (unidentified; typical Wiseman) arguing with each other about whether a leg should be raised or lowered. It’s all very amusing and quite lovable, like the old dancers in that most excellent of ballet films, Ballets Russes, by Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller.

Impossible to even think about that now, which must mean Portland’s evolving into a city at last.

Impossible to even think about that now, which must mean Portland’s evolving into a city at last. Another big player in those midcentury years, sculptor and printmaker Manuel Izquierdo, died in July. Notable (like so many of his contemporaries) as a teacher as well as an artist, he was also one of the artists who connected the Northwest’s sometimes insular scene to international ideas. He was born in Madrid, left Spain during the Civil War, and spent most of his adult life in Portland. But he brought a European spirit with him.

Another big player in those midcentury years, sculptor and printmaker Manuel Izquierdo, died in July. Notable (like so many of his contemporaries) as a teacher as well as an artist, he was also one of the artists who connected the Northwest’s sometimes insular scene to international ideas. He was born in Madrid, left Spain during the Civil War, and spent most of his adult life in Portland. But he brought a European spirit with him. Hoving was a swashbuckler, a showman, a democratizer, maybe even something of a pirate. When he took over the great Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan in 1967, at the age of 35, he declared it moribund and set out to make it the most popular show in town.

Hoving was a swashbuckler, a showman, a democratizer, maybe even something of a pirate. When he took over the great Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan in 1967, at the age of 35, he declared it moribund and set out to make it the most popular show in town.