So, what does a possible breakup of the Episcopal Church in the United States have to do with the price of tickets in Portland? Nothing, maybe. Then again, maybe something, after all.

So, what does a possible breakup of the Episcopal Church in the United States have to do with the price of tickets in Portland? Nothing, maybe. Then again, maybe something, after all.

At first blush this morning’s news in the New York Times that a small group of conservative bishops has declared itself divorced from the American branch of the church (though not from global Anglicanism) doesn’t seem to have much to do with the world of art. The dispute seems to be mostly over American Episcopalians’ welcoming of gay and lesbian parishioners, and conservatives’ continuing disgruntlement over the ordination five years ago of an openly gay bishop in New Hampshire. The temptation is to scratch your head over how, in a supposedly sophisticated spiritual communion in the year 2008, homosexuality can still be a bitterly divisive issue, to declare that 20 years from now the children of the breakaway churchmen and churchwomen will be similarly scratching their heads trying to figure out what in the world their parents were thinking, and move on. Their church, their problem: Every great social movement has its backwater of protest.

But. If this really goes through, almost inevitably there will be lawsuits over which faction owns church property when a local church breaks away from the larger group. And because churches enjoy tax-exempt status, the possibility of spillover to the nonprofit world isn’t out of the question. When this fight hits the courts the question of why churches aren’t taxed will be raised in a lot of quarters. And although we all complain about the lack of public support for the arts, the fact remains that our local and national governments do provide nonprofit arts groups (which in a city like Portland means just about all of them) with the very big financial advantage that nonprofit status entails — a public underwriting, in the fine print of the ledger books, of the arts and other community-based endeavors. Don’t expect, in our current atmosphere of bailouts, defaults, rising unemployment and scary recession, that this form of public spending won’t be challenged, too. Especially amid the rising libertarian movement, which looks suspiciously on any and all hands it thinks might be dipping into its pocket.

With the recession already coming down heavily on arts groups — for instance, Oregon Ballet Theatre has dropped live music from the majority of this month’s performances of The Nutcracker, a major step backward for a company that’s been making a name for itself nationally — an added hit in the tax and underwriting pocket could be devastating. And don’t think it can’t happen. A few years ago a judge on the Oregon Coast decided that the tax breaks to a small community theater in Lincoln City weren’t legal. If he’d prevailed (he didn’t) the entire structure of arts support in Oregon would have been jeopardized. So, onward, cultural soldiers. Don’t take anything for granted. Keep in touch with those city council members and state legislators. And keep making your case.

***********************************************

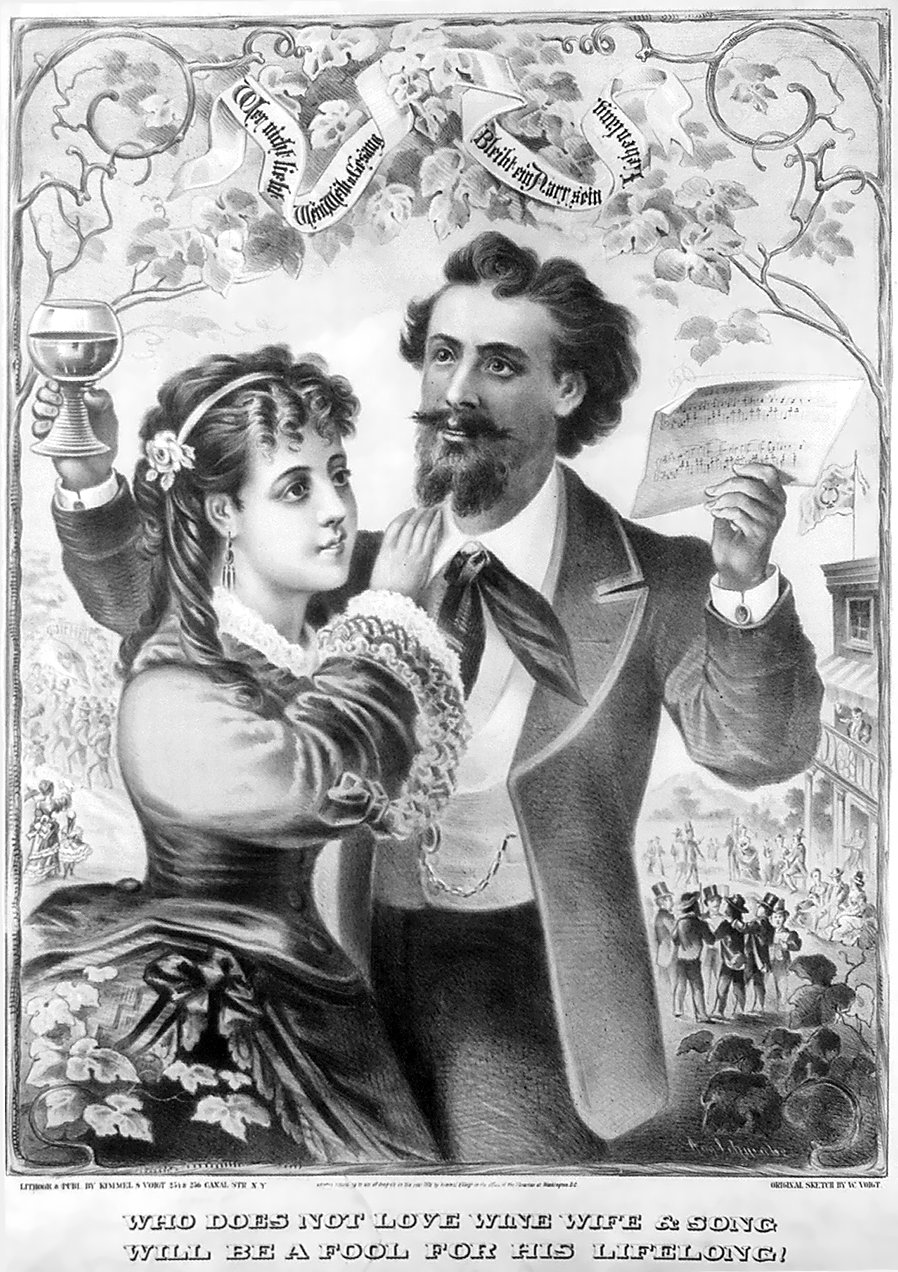

On a bubblier note, a friend points out that Prohibition ended 75 years ago Friday — on Dec. 5, 1933 — and we’ll drink to that. The 18th Amendment, which ironically put a lot of the roar into the Roaring Twenties, had gone into effect on June 16, 1920, and had the effect mainly of manufacturing a lot of criminals out of previously law-abiding folks. It also led to a thriving moonshine industry, the possible naming of the great Li’l Abner character Moonbeam McSwine (and the comic strip’s house tipple, Kickapoo Joy Juice), and those eventual twin pillars of American pop culture, the movie and song versions of Thunder Road.

On a bubblier note, a friend points out that Prohibition ended 75 years ago Friday — on Dec. 5, 1933 — and we’ll drink to that. The 18th Amendment, which ironically put a lot of the roar into the Roaring Twenties, had gone into effect on June 16, 1920, and had the effect mainly of manufacturing a lot of criminals out of previously law-abiding folks. It also led to a thriving moonshine industry, the possible naming of the great Li’l Abner character Moonbeam McSwine (and the comic strip’s house tipple, Kickapoo Joy Juice), and those eventual twin pillars of American pop culture, the movie and song versions of Thunder Road.

So, celebrate — quietly, moderately, enjoyably — tomorrow night. We’re putting a bottle of Saint-Hillaire 2004 Blanquette de Limoux brut in the Art Scatter refrigerator right now.

******************************************************

It’s no secret that the old Oregon Biennial was about as high on Bruce Guenther’s list of priorities as his shoelaces: Asked once what he’d like to do with the Biennial, the Portland Art Museum‘s chief curator grinned and said, “Kill it off.”

It’s no secret that the old Oregon Biennial was about as high on Bruce Guenther’s list of priorities as his shoelaces: Asked once what he’d like to do with the Biennial, the Portland Art Museum‘s chief curator grinned and said, “Kill it off.”

Eventually, he did.

But if the state of Oregon doesn’t have a broad-overview showcase of the visual arts any more, or even the more narrowly focused showcase that the Biennial became before it quivered and died, the Pacific Northwest does. Today the Tacoma Art Museum announced the featured artists for its ninth annual Northwest Biennial, and followers of the Portland art scene will recognize a lot of the talent.

Michael Brophy (that’s his highway scene above), Linda Hutchins, Victor Maldonado, Stephanie Robison and Susan Seubert all made the cut of 24 (from 543 entries), as did Tannaz Farsi and Chang-Ae Song of Eugene. All of the others are from Washington state, mostly Seattle: Rick Araluce, Gala Bent, Jack Daws, Eric Elliott, Sarah Hood, Denzil Hurley, Robert Jones, Michael Kenna, Doug Keyes, Isaac Layman, Zhi Lin, Micki Lippe, Margie Livingston, Deborah Moore, Susan Robb, Ross Sawyers, Scott Trimble. No one from Idaho or Montana was chosen.

The picks were made by Tacoma museum curator Rock Hushka and Alison de Lima Greene, contemporary curator for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. You can zip up the freeway and see the show between Jan. 31 and May 25.

More to the point, both plays are about the American character, as measured through real historical characters and events, and both deal with the gap between the buoyant public perception and the tougher reality of the historic episodes they choose to portray.

More to the point, both plays are about the American character, as measured through real historical characters and events, and both deal with the gap between the buoyant public perception and the tougher reality of the historic episodes they choose to portray.