Like so many great art forms, dance is a series of interlinked relationships and memories, a tradition that continually redefines and reinvents itself. It lives in the past, and the present, and the future, and its story is written in the memories and associations of open-hearted observers as well as the muscles of dancers and the patterns in choreographers’ minds.

Dance writer Martha Ullman West, one of our best observers, took in last Friday’s Dance United, and for her it was like biting into a madeleine: The reminiscences and connections just began to flow. Somehow, no matter how far-flung, they all looped back to Oregon Ballet Theatre, its history and successes, and this extraordinary event to keep the company alive and vital.

Here is the link to Martha’s review in The Oregonian of the performance. And here, below, is her more personal report on what it all meant:

———————————————————————-

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Dancers came from Texas, Utah, Massachusetts, Canada, Washington state, California, Chicago, Idaho, and that other geographical location, in New York called Downtown, here designated as Portland’s modern and contemporary dance community.

The gifts they brought were generous: their talent and their time. And they were welcomed to Keller Auditorium with the same enthusiasm as Obama’s supporters do and did, reaching into their wallets with many relatively small donations to keep Oregon Ballet Theatre alive. On Tuesday, OBT had in hand $720,000 of the $750,000 it needs to make up THIS season’s deficit.

I’ve been watching dance in Portland and elsewhere for more decades that I wish to reveal, and professionally since 1979, when I wrote an essay on postmodern dance in New York for Dance Magazine. In so many ways, this gala triggered some Proustian moments, also making me think of all the ways that dance and dancers are connected to each other.

Linda Austin’s thoroughly postmodern “anybody-can-dance, any-movement-on-stage-is-valid” Boris & Natasha Dancers (on catnip) took me back to New York’s SoHo and a performance created by Karole Armitage consisting of a group of dancers on their hands and knees, painting stripes on the floor, in humorless silence. They were not skilled at either painting or dancing, but it was the same democratic approach to the art form as Austin’s new dance, which featured such pillars of the Portland community as two Bragdons (Peter and David), Scott Bricker, James Harrison and Peter Ames Carlin galumphing across the stage, one of them wearing red sneakers that I wondered if he’d borrowed from White Bird’s Paul King. (Armitage, you may remember, also made work on OBT’s dancers on James Canfield’s watch.)

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

And I thought about Mark Goldweber, ballet master at OBT under Canfield, then for some years at the Joffrey, and now at Ballet West. (He gave the only authentic performance in Robert Altman’s dance film The Company, in my view.) I wondered what Mark thinks about the way Adam Sklute, now Ballet West’s artistic director, staged this version of the White Swan pas de deux.

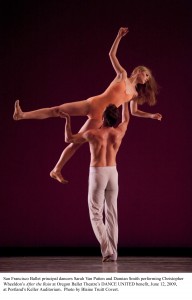

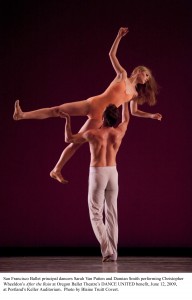

When I encountered this ballet’s real-life Prince Siegfried, Christopher Ruud, at OBT’s studios earlier in the week, I spoke with him about his father, who had helped Todd Bolender at Kansas City Ballet (Bolender is the subject of a book I’m working on). Ruud told me he had staged one of his father’s pieces on the company several years ago.

Continue reading Martha Ullman West on Dance United: a personal take →

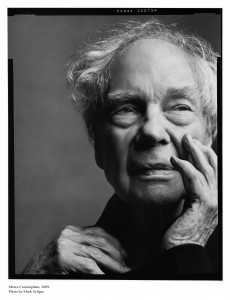

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche. Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans. The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

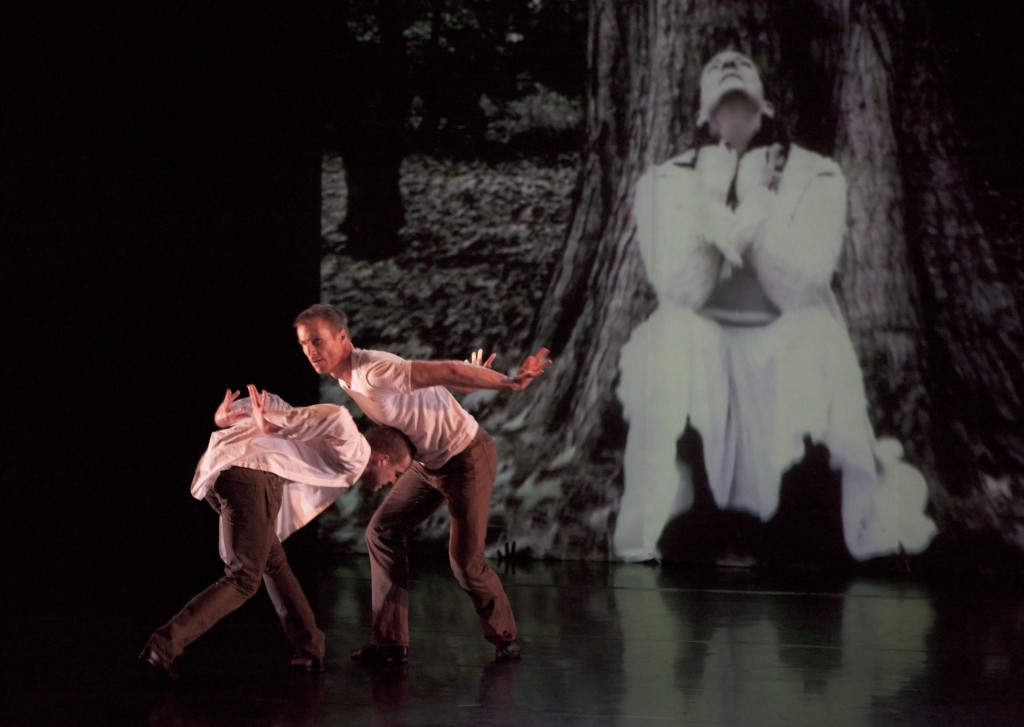

At the conclusion of Bete Perdue,

At the conclusion of Bete Perdue,