Here’s the thing. Arts people have been around a very long time, and no matter how hard you kick ’em around, they keep popping back up.

Here’s the thing. Arts people have been around a very long time, and no matter how hard you kick ’em around, they keep popping back up.

In Portland recently, people ponied up $120,000 in a single week to save the annual summer Washington Park music festival. They tossed in more than $850,000 to keep Oregon Ballet Theatre from folding.

In the middle of the worst recession/depression since the 1930s, people are somehow helping to pay for things they believe in, and they just keep going to shows. Maybe they’re looking for bargains. But they’re looking, and they’re going.

It’s an ingrained human need, as John Noble Wilford suggests in this morning’s New York Times. Wilford, the Times’ fine science writer, reports on the discovery of a five-hole bone flute in a cave in what’s now southwestern Germany. It’s a sophisticated instrument, apparently with harmonic possibilities not too far removed from a modern flute’s. And it’s at least 35,000 years old — maybe 40,000. It was discovered, Noble reports, “a few feet away from the carved figure of a busty, nude woman, also around 35,000 years old.” As the researchers keep digging I’m hoping they’ll discover the remains of an ancient flagon and complete the Ice Age trifecta: wine, women and song.

So, yes, right now a lot of artists have their hands out. And what’s amazing to me is that so many people are pausing among their own economic problems and doing what they can. Another example: The Portland Ballet, the “other” classically oriented dance company in town, has collected $15,000 from a public drive specifically so it can have live music for its annual performance of the holiday-season ballet La Boutique Fantasque. I don’t know if this is exactly what Barry Johnson meant in his recent Portland Arts Watch post about democratizing the arts, but it’s sure active and participatory.

So just for fun, let’s make the argument that art is as much of a human need as food — or, if that’s too rash, that the urge to make art is as ingrained in the human psyche as the necessity to eat is imprinted on the human body. Sure, you can survive without art. But the artistic impulse is there, I’ll suggest, in your heartbeat. Everyone’s got rhythm.

And that link between food and art brings me to Sojourn Theatre and its upcoming benefit, A Very American Breakfast, which is happening 7:30-9 in the morning on Wednesday, July 1, at Disjecta, that big inviting space for all sorts of things in the percolating old Kenton neighborhood of North Portland. (Disjecta is having its own first-anniversary party for its Kenton home from 8 to 11 Saturday, June 27; no cover, cash bar.)

Sojourn is a Portland-based company that tours the country, developing and performing community-based plays that usually coalesce around specific themes. For the last year, among a myriad of other activities, it’s been working on a new piece called On the Table that looks at food, and how it’s grown and distributed, and the choices we make about it, and the impact it has on various communities. A lot of field reporting (in this case, literally) goes into a typical Sojourn show, and that takes time and resources. Company director Michael Rohd figures the project has another year to go: “The show will happen Summer 2010 simultaneously in PDX and a small town 50 miles from PDX, and explores the urban/rural conversation in Oregon, culminating with a bus trip for both audiences and a final act at an in-between site,” he says.

Sojourn is a Portland-based company that tours the country, developing and performing community-based plays that usually coalesce around specific themes. For the last year, among a myriad of other activities, it’s been working on a new piece called On the Table that looks at food, and how it’s grown and distributed, and the choices we make about it, and the impact it has on various communities. A lot of field reporting (in this case, literally) goes into a typical Sojourn show, and that takes time and resources. Company director Michael Rohd figures the project has another year to go: “The show will happen Summer 2010 simultaneously in PDX and a small town 50 miles from PDX, and explores the urban/rural conversation in Oregon, culminating with a bus trip for both audiences and a final act at an in-between site,” he says.

The benefit breakfast costs $50 (you can make a reservation here, or if that’s too much or too little or you’re going to be out of town, make a donation) and will feature food from Phresh Organic Catering. Disjecta is at 8371 N. Interstae Ave., Portland.

Sojourn doesn’t make a habit of putting its hand out, but there comes a time and place. Here’s part of what Rohd had to say when he spread the word:

“So, we are busy.

And we don’t have a building.

And we are engaged in the most ambitious project of our nearly ten years together.And, its going to be tough.

This moment right now is tough.

But we believe — go big, or go home.”

In the meantime, breakfast in the shadow of Kenton’s giant Paul Bunyan statue sounds good.

**************************

Another way to look at food and art and cities and rural life: Froelick Gallery‘s exhibit Town & Country: Oregon at 150, which continues through July 11 at the gallery, 714 N.W. Davis St, just off Broadway. This juried group show takes a look at Oregon through its urban/rural geographical divide, which sometimes is a connection as well. That’s Eric Bowman’s 2007 painting “Oregon Farm” above.

Who knows? Maybe someone’s sitting behind the barn, playing a five-hole bone flute. And maybe that’s just all right.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8. But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

The show began with TouchMonkey, in the persons of Carolyn Stuart and Patrick Gracewood, who are longtime practitioners of Contact Improvisation, a form based on trust and the ability to make on-the-spot kinetic connections. Stuart was wearing a black cloth over her eyes, which meant her responses to Gracewood were entirely by touch and contact. Their duet, titled Special Alembics, (nice pun!) was performed to music played live by Eddy Deane, Alley Teach, and David Lyles of The Contact Lounge Band.

The show began with TouchMonkey, in the persons of Carolyn Stuart and Patrick Gracewood, who are longtime practitioners of Contact Improvisation, a form based on trust and the ability to make on-the-spot kinetic connections. Stuart was wearing a black cloth over her eyes, which meant her responses to Gracewood were entirely by touch and contact. Their duet, titled Special Alembics, (nice pun!) was performed to music played live by Eddy Deane, Alley Teach, and David Lyles of The Contact Lounge Band.

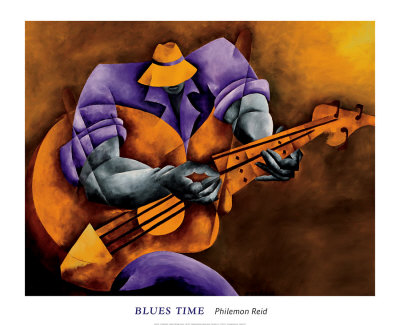

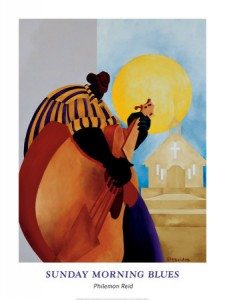

And through it all he did the thing he loved to do, which was to paint and sculpt images of the African American musicians who played the blues and jazz. He often listened to Coltrane or Miles or Ella while he was making his own art.

And through it all he did the thing he loved to do, which was to paint and sculpt images of the African American musicians who played the blues and jazz. He often listened to Coltrane or Miles or Ella while he was making his own art. While Art Scatter was spending Thursday in the Columbia Gorge visiting the

While Art Scatter was spending Thursday in the Columbia Gorge visiting the  PNCA at 100: Two good pieces on the

PNCA at 100: Two good pieces on the Mr. Salinger does know the legal profession, and in pursuit of his vaunted rights has made liberal use of it over the years. The New York Times reports

Mr. Salinger does know the legal profession, and in pursuit of his vaunted rights has made liberal use of it over the years. The New York Times reports  Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

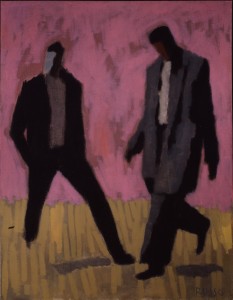

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans. The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process. The smashing success of last Friday’s

The smashing success of last Friday’s

As I realized I was having

As I realized I was having