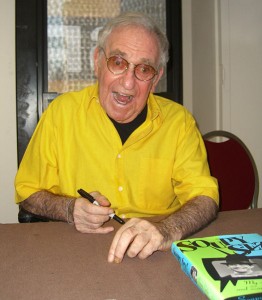

ABOVE: “Orpheus and Eurydice,” Nicolas Poussin, 1650-51. Musee de Louvre, Paris. INSET: Philip Glass, composer of “Orphee.” Wikimedia Commons.

DON’T LOOK BACK. Bob Dylan gave that sage advice, possibly after considering the experiences of Lot’s wife, who turned into a pillar of salt after peeking back at the lost pleasures of Sodom, and of Orpheus, who doomed his wife to the Underworld by glancing over his shoulder as he was leading her back from the far side of the River Styx.

Well, Mr. Scatter’s made a couple of rash decisions lately, and he’s determined not to look back: Mrs. Scatter would be seriously ticked off if she turned into a salt lick in Hell. Onward and forward, eyes on the prize.

*************

RASH DECISION #1: I’ve agreed to be one of Portland Opera’s speed-bloggers on Friday night at the opening performance of Philip Glass‘s Orphee, a 1991 opera (premiered in 1993) based on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice and on Jean Cocteau‘s mysteriously poetic 1949 film adaptation, also called Orphee. Portland Opera‘s production will be the opera’s West Coast premiere.

What this means is that, while you’re filing into Keller Auditorium before the show, I’ll be in the lobby seated at a table with several other bloggers, dashing out immediate impressions and committing them to cyberspace before I have time to repent and delete. I’ll have a backstage tour beforehand, and yes, I do get to see the show, after which I’ll dash back to my laptop and blog some more. This will be either the rough draft of history or outtakes of an unsifted mind, but I will Not. Look. Back.

What this means is that, while you’re filing into Keller Auditorium before the show, I’ll be in the lobby seated at a table with several other bloggers, dashing out immediate impressions and committing them to cyberspace before I have time to repent and delete. I’ll have a backstage tour beforehand, and yes, I do get to see the show, after which I’ll dash back to my laptop and blog some more. This will be either the rough draft of history or outtakes of an unsifted mind, but I will Not. Look. Back.

To prepare, I’ll be on hand for Creativity and Collaboration: An Evening with Philip Glass, a Tuesday night gathering with the composer at the Portland Art Museum’s Kridell Auditorium, where Glass will talk about his music and career. The evening’s sponsored by the opera, the Northwest Film Center (which screened Cocteau’s Orphee last night) and the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, which has a long history with Glass. I’ll also get a chance to talk with Glass in a group interview Tuesday morning with a quartet of musically savvy Portland writers: Marty Hughley, Bob Kingston, James Bash and Brett Campbell. Glass’s trip to Portland will be pretty brief: By opening night of Orphee he’ll already be in Mexico City, performing some of his chamber music.

My fellow bloggers (sounds like the beginning of a political speech) on opening night will be actress/rock star Storm Large, man-about-town Byron Beck, arts marketer extraordinaire Cynthia Fuhrman, and someone (not sure who) from PICA. Our compensation, I’m told, will be “plenty of beer, nuts and cookies during intermission.”

I don’t have a Facebook account and I do not Twit, so here’s how it’ll work: I’ll start a Glass/Orphee post on Friday evening and write everything on it, hitting “publish” at regular intervals so the post gets longer as the night goes on. I’ll mark each new entry by its time, so you can get a sense of the “running” part of the running commentary.

And I will not look over my shoulder. Someone might be gaining on me.

*************

RASH DECISION #2: My friend Susan Jonsson sits on the board of Well Arts Institute, a group of theater and other artists who use writing and theater to, as they put it, “generate well-being, hope, and meaning for people in life-altering health situations.” Some very talented people are involved in this project, and the transformational possibilities of storytelling are near the core of what they do.

So when Susan asked whether I’d be a guest performer in Well Arts’ fall show, Voices of Our Elders, I said yes. The process is fascinating. Well Arts people do a 10-week workshop on memoir and creative writing with older people in care centers, listening to their stories, transcribing them, helping them shape them. The result is a show of monologues and a few dialogues from people looking back on their lives, on what was important, and contemplating what’s to come. It’s a fundamental form of personal history and an emotionally involving form of documentary theater.

So when Susan asked whether I’d be a guest performer in Well Arts’ fall show, Voices of Our Elders, I said yes. The process is fascinating. Well Arts people do a 10-week workshop on memoir and creative writing with older people in care centers, listening to their stories, transcribing them, helping them shape them. The result is a show of monologues and a few dialogues from people looking back on their lives, on what was important, and contemplating what’s to come. It’s a fundamental form of personal history and an emotionally involving form of documentary theater.

Well Arts director Lorraine Bahr has assembled a good cast to present these stories: John Morrison, Ritah Parrish, Deirdre Atkinson, Steve Boss, Andrea White, Wendy Westerwelle and writer-performer Vince Falco. Each performance will also include a revolving lineup of guest readers: singer Shirley Nanette; actors Delight Lorenz, Luisa Sermol, Tom Gough and Susan Jonsson; onetime Broadway hoofer and legendary Portland director/teacher Jack Featheringill; Oregon Arts Commissioner and longtime theater supporter Julie Vigeland; and me.

I went to a rehearsal on Halloween afternoon at the Olympic Mills Commerce Center, a rehab development housing arts, food and design businesses at 107 S.E. Washington St., near the riverfront in the close-in East Side light-industrial district. This is where the show will be, and it’s an interesting new creative hub, worth visiting: We rehearsed in front of the Zimbabwe Artists Project, a space covered with gorgeous appliques and fabric paintings created by women of the Weya region of Zimbabwe.

Voices of Our Elders runs at 3 and 7 p.m. Saturdays, Nov. 7 and 14; and at 3 p.m. Sundays, Nov. 8 and 15. I’ll do my reading — a piece I like quite a bit, called The Day I Went to Enlist — at the Nov. 14 matinee. Ticket and other info here.

He made the announcement today on his Portland Arts Watch blog, where for the past year or so he’s, well, kept watch on the arts in Portland. Lots of terrific ideas and elegant writing have spun out of PAW in its print and online versions.

He made the announcement today on his Portland Arts Watch blog, where for the past year or so he’s, well, kept watch on the arts in Portland. Lots of terrific ideas and elegant writing have spun out of PAW in its print and online versions.

Partly because of weather and isolation, Maryhill is a seasonal museum, and it takes its annual break Nov. 15 before starting up again in spring, on the ides of March. That gives you a couple of weeks to make the drive out the Gorge: It’s a little more than 100 miles east of Portland, about the same distance as Eugene, but a much more interesting drive.

Partly because of weather and isolation, Maryhill is a seasonal museum, and it takes its annual break Nov. 15 before starting up again in spring, on the ides of March. That gives you a couple of weeks to make the drive out the Gorge: It’s a little more than 100 miles east of Portland, about the same distance as Eugene, but a much more interesting drive.

What this means is that, while you’re filing into Keller Auditorium before the show, I’ll be in the lobby seated at a table with several other bloggers, dashing out immediate impressions and committing them to cyberspace before I have time to repent and delete. I’ll have a backstage tour beforehand, and yes, I do get to see the show, after which I’ll dash back to my laptop and blog some more. This will be either the rough draft of history or outtakes of an unsifted mind, but I will Not. Look. Back.

What this means is that, while you’re filing into Keller Auditorium before the show, I’ll be in the lobby seated at a table with several other bloggers, dashing out immediate impressions and committing them to cyberspace before I have time to repent and delete. I’ll have a backstage tour beforehand, and yes, I do get to see the show, after which I’ll dash back to my laptop and blog some more. This will be either the rough draft of history or outtakes of an unsifted mind, but I will Not. Look. Back. So when Susan asked whether I’d be a guest performer in Well Arts’ fall show, Voices of Our Elders, I said yes. The process is fascinating. Well Arts people do a 10-week workshop on memoir and creative writing with older people in care centers, listening to their stories, transcribing them, helping them shape them. The result is a show of monologues and a few dialogues from people looking back on their lives, on what was important, and contemplating what’s to come. It’s a fundamental form of personal history and an emotionally involving form of documentary theater.

So when Susan asked whether I’d be a guest performer in Well Arts’ fall show, Voices of Our Elders, I said yes. The process is fascinating. Well Arts people do a 10-week workshop on memoir and creative writing with older people in care centers, listening to their stories, transcribing them, helping them shape them. The result is a show of monologues and a few dialogues from people looking back on their lives, on what was important, and contemplating what’s to come. It’s a fundamental form of personal history and an emotionally involving form of documentary theater.

The Portland Art Museum, in a show assembled by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, heralds the arrival of China Design Now. (“Now” is really then, but a recent then: The show was aimed to coincide with last year’s Beijing Olympics and to capture the wave of commercial and aesthetic design in the world’s most populous country, a wave that inevitably has since washed on.)

The Portland Art Museum, in a show assembled by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, heralds the arrival of China Design Now. (“Now” is really then, but a recent then: The show was aimed to coincide with last year’s Beijing Olympics and to capture the wave of commercial and aesthetic design in the world’s most populous country, a wave that inevitably has since washed on.) I remember that film well — the extreme, almost ecstatic enthusiasm of China’s musicians; Stern’s encouragement and good will; his sense that the older students and musicians he encountered — the ones who’d spent years being “reeducated” in peasant labor and cut off from contact with Western music — seemed technically correct but lacking passion in their playing.

I remember that film well — the extreme, almost ecstatic enthusiasm of China’s musicians; Stern’s encouragement and good will; his sense that the older students and musicians he encountered — the ones who’d spent years being “reeducated” in peasant labor and cut off from contact with Western music — seemed technically correct but lacking passion in their playing.

I don’t remember much about Sales. He was mostly a television figure — he had an extremely popular comedy show — and in the 1960s and ’70s I watched even less TV than I do now. But in the same way you know Britney Spears even if you couldn’t pick out one of her songs from a criminal lineup, I knew Soupy — that dopey elastic mug, the fading pie-in-the-face routine that he revived … well, 20,000 times.

I don’t remember much about Sales. He was mostly a television figure — he had an extremely popular comedy show — and in the 1960s and ’70s I watched even less TV than I do now. But in the same way you know Britney Spears even if you couldn’t pick out one of her songs from a criminal lineup, I knew Soupy — that dopey elastic mug, the fading pie-in-the-face routine that he revived … well, 20,000 times. Physical comedy — and what is more physical than smacking a pie in someone’s kisser for laughs? — has been around at least since the early-Renaissance beginnings of commedia dell’arte. Shakespeare thrived on it. You find it everywhere from kabuki to Punch and Judy shows to I Love Lucy and the buff posturings of pro wrestling. Imagine Hulk Hogan as Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The tradition’s continued, if not often with the aid of actual pies, with the likes of Robin Williams (in his astonishing “nanu nanu” phase), John Cleese, John Bulushi, Bette Midler (non-weepy version), Danny DeVito and, I am sorry to point out, Adam Sandler.

Physical comedy — and what is more physical than smacking a pie in someone’s kisser for laughs? — has been around at least since the early-Renaissance beginnings of commedia dell’arte. Shakespeare thrived on it. You find it everywhere from kabuki to Punch and Judy shows to I Love Lucy and the buff posturings of pro wrestling. Imagine Hulk Hogan as Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The tradition’s continued, if not often with the aid of actual pies, with the likes of Robin Williams (in his astonishing “nanu nanu” phase), John Cleese, John Bulushi, Bette Midler (non-weepy version), Danny DeVito and, I am sorry to point out, Adam Sandler. A project of the Portland State University Writing Center, PDX Writer Daily had taken a long summer sabbatical that stretched into fall, and so I hadn’t checked it in a while.

A project of the Portland State University Writing Center, PDX Writer Daily had taken a long summer sabbatical that stretched into fall, and so I hadn’t checked it in a while. That’s #83? Hmm. Well…okay. It actually does feel kind of 83rd-ish, doesn’t it? They might be right on that one.

That’s #83? Hmm. Well…okay. It actually does feel kind of 83rd-ish, doesn’t it? They might be right on that one.

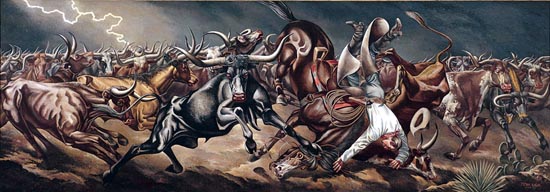

The rush began during that final fade, when the proper response was to sit still and let the emotional accumulation of this three-and-a-half-hour American journey sink in. It hit full throttle when the lights came up for cattle call … I mean, curtain call. As many in the audience were rising to their feet to applaud the work of this talented company of actors, many others were bumping and bruising their ways to the aisles, trodding on toes, trailing their belongings, urging their fellow longhorns on so they could get out first. Show’s over. Drinks and bathrooms calling.

The rush began during that final fade, when the proper response was to sit still and let the emotional accumulation of this three-and-a-half-hour American journey sink in. It hit full throttle when the lights came up for cattle call … I mean, curtain call. As many in the audience were rising to their feet to applaud the work of this talented company of actors, many others were bumping and bruising their ways to the aisles, trodding on toes, trailing their belongings, urging their fellow longhorns on so they could get out first. Show’s over. Drinks and bathrooms calling.