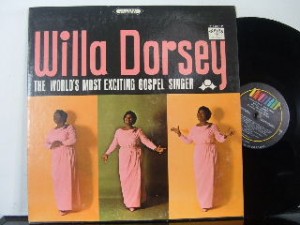

Sad news in this morning’s Oregonian, as reported by Nancy Haught: Willa Dorsey, the great gospel singer who lived in Portland between her worldwide rambles, died Jan. 5 after a series of strokes. She was 75. Her funeral will be at 11 a.m. Wednesday at the International Fellowship Family, 4401 N.E. 122nd Ave., Portland.

Despite her high-flying career, Dorsey wasn’t terrifically well-known in her adopted home town — except in church circles and among fellow musicians. She was a sweet woman with an amazing voice, and a fine pianist, and she somehow managed to combine down-home humility with a regal air. I spent some time with her in 1991, working on some stories for The Oregonian on gospel music and its influence on American art and culture, and I’ve remembered her fondly ever since, although in the succeeding years I ran into her only two or three times. In her memory — and to introduce Willa to those of you who never knew her or her music — I’m going to post two stories that originally ran in The Oregonian on Dec. 22, 1991. These are time capsules, but they get at something of the spirit of Willa’s music and remarkable life. This post is a profile of Willa; the one below is its companion story about gospel music, and it includes more information about her. Goodbye, Willa. As you would have said, God bless.

———————————————————————

It might have been 1939, she thinks. Young Willa Dorsey, maybe 6 years old, was playing outside, idly running through a few tunes she’d heard at church.

It might have been 1939, she thinks. Young Willa Dorsey, maybe 6 years old, was playing outside, idly running through a few tunes she’d heard at church.

Suddenly she heard her mother, alert and mildly worried, calling sharply from inside:

“Who’s out there with you?”

“I said, `No one,’ ” Dorsey recalls with amusement.

“She said, `There has to be. I heard someone singing.’

“I said, `That’s me.’ ”

Dorsey pauses, then leaps into her punchline:

“And she didn’t believe me!”

No wonder: It just sounded too good. But a couple of quick demonstrations convinced Mr. and Mrs. Dorsey that their daughter had been hiding a special talent — “a God-given gift,” as Willa firmly puts it. Soon she was singing on stages in her home town of Atlanta, Ga.

For half a century, she hasn’t stopped.

Now 58, Dorsey is Portland’s most prominent gospel singer, though most of her performances are out of town. She can look back on a career that’s taken her to national television audiences, to presidential prayer breakfasts (“Mrs. Bush and I are friends,” she says offhandedly. “We correspond.”), to featured roles in several Billy Graham crusades, and around the world for acclaimed performances in countries as far-flung as Germany, Sri Lanka, Brazil and Japan. She’s as comfortable with a 90-piece symphony orchestra or a 2,000-voice choir as she is alone behind a piano keyboard.

And she’s still singing those songs she heard in church.

Continue reading Willa Dorsey, 1933-2009: Farewell to God’s golden voice