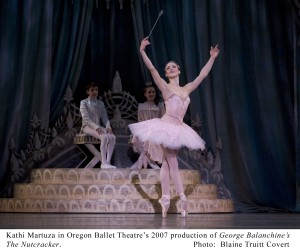

Nobody knows her Marzipans from her Sugarplum Fairies as well as Martha Ullman West, the distinguished dance writer and charter member of Friends of Art Scatter. We here at Scatter Central are pleased as holiday punch — and with the right additives, that’s pretty darned pleased — to turn our space over to her for some insights into Oregon Ballet Theatre’s “The Nutcracker” and the long line of Nutcrackers leading up to it. Read on!

When George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker premiered at New York City Center in 1954, critic Edwin Denby reported that a “troubled New York poet sighed, “I could see it every day, it’s so deliciously boring.” I thought of that remark while viewing the same choreography, excellently danced, when Oregon Ballet Theatre opened its current run on Friday. I think the poet, not named by Denby, but possibly W.H. Auden, must have made his backhanded comment at intermission, following the first act party scene. I don’t know if he ever went back, but I have, again and again, in many versions, including a Nutcracker God-help-me on ice, and the boredom becomes less delicious each time.

When George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker premiered at New York City Center in 1954, critic Edwin Denby reported that a “troubled New York poet sighed, “I could see it every day, it’s so deliciously boring.” I thought of that remark while viewing the same choreography, excellently danced, when Oregon Ballet Theatre opened its current run on Friday. I think the poet, not named by Denby, but possibly W.H. Auden, must have made his backhanded comment at intermission, following the first act party scene. I don’t know if he ever went back, but I have, again and again, in many versions, including a Nutcracker God-help-me on ice, and the boredom becomes less delicious each time.

So on Friday, my mind wandered a bit — well, more than a bit — during that family party, notwithstanding adorable children in their party clothes, naughty Fritz and dancing dolls, all of whom performed just as they should have, harking back to the ghosts of Nutcrackers past — specifically James Canfield’s at OBT and Todd Bolender’s, which is still being performed by Kansas City Ballet. Both Canfield and Bolender (who danced in Balanchine’s 1954 production) have enlivened the party considerably, the former with mechanical dolls that are somewhat reminiscent of Dorothy’s companions in the Wizard of Oz (and they accompany Marie on her journey, in Canfield’s case to the palace of the Czar) and the latter with hordes of small boys galloping around the staid gathering tooting toy trumpets, and less formal social dances than Balanchine’s.

Nevertheless, there are elements of Balanchine’s party that I love and look for, particularly the Grandfather dance, which begins in stately decorum and concludes with a lively little pas de deux by the Grandmother and Uncle Drosselmeier, here performed by apprentice Ashley Smith and principal dancer Artur Sultanov, who will be seen in later performances as the Sugar Plum Fairy’s Cavalier. Moreover, his Marie is performed by a little girl and not an adult dancer pretending to be one. Julia Rose Winett, who danced the role on Friday night, has a jump that makes you think she has springs in her slippers. She can act, too. You know she’s scared to death during the battle of the mice and toy soldiers, even though the Mouse King really doesn’t look very frightening.

Nevertheless, there are elements of Balanchine’s party that I love and look for, particularly the Grandfather dance, which begins in stately decorum and concludes with a lively little pas de deux by the Grandmother and Uncle Drosselmeier, here performed by apprentice Ashley Smith and principal dancer Artur Sultanov, who will be seen in later performances as the Sugar Plum Fairy’s Cavalier. Moreover, his Marie is performed by a little girl and not an adult dancer pretending to be one. Julia Rose Winett, who danced the role on Friday night, has a jump that makes you think she has springs in her slippers. She can act, too. You know she’s scared to death during the battle of the mice and toy soldiers, even though the Mouse King really doesn’t look very frightening.

Continue reading Martha Ullman West on the Ghost of Nutcrackers Past