“How could they say ‘partial’ nudity?” Gentleman No. 1 asked wryly. “They were totally naked.”

Gentlewoman No. 1 nodded in agreement. “Doesn’t make sense, does it?”

“Well,” Gentleman No. 2 replied, “they were all the way naked, but not all of the time. So maybe it was ‘partial’ nudity in the sense that sometimes they had clothes on and sometimes they didn’t.”

It was Wednesday night in the stripped-down lobby of the Eastbank Annex, and a gaggle of dance aficionados were talking about the piece they’d just seen, Daniel Leveille Danse’s Crepuscule des Oceans, or Twilight of the Oceans. Their attention had shifted to the curious easel-mounted announcement perched beside them in the lobby.

The sign’s message, or warning, that the performance included naked bodies had been hastily amended: A small piece of paper with the scrawled word Full had been taped over the carefully printed original word Partial, directly in front of the word Nudity. The smaller paper was taped on only at the top, so it worked like a flap, and as they were talking one of the group was flipping it back and forth — Partial-Full-Partial-Full-Partial — like a piece of sly performance art. Everyone laughed, which was more than anyone did during the show itself.

The sign’s message, or warning, that the performance included naked bodies had been hastily amended: A small piece of paper with the scrawled word Full had been taped over the carefully printed original word Partial, directly in front of the word Nudity. The smaller paper was taped on only at the top, so it worked like a flap, and as they were talking one of the group was flipping it back and forth — Partial-Full-Partial-Full-Partial — like a piece of sly performance art. Everyone laughed, which was more than anyone did during the show itself.

So it’s come to this: In the ever more intellectualized world of contemporary performance, even skin’s become a mind game. This was opening night of the first show in White Bird’s Uncaged dance season, and if the sign was meant to defuse any shocked sensibilities it was probably superfluous.

This crowd seemed as if it knew very well what it was getting into, and it wasn’t going to let a little nudity throw it for a loop. Indeed, the nudity — and the opportunity to view it with an air of studied nonchalance — was undoubtedly part of the draw.

“I really liked the lighting,” Mr. Scatter found himself saying to a friend, and she nodded. Neither of them bothered to bring up how those Caravaggio marble effects were bouncing off of finely sculpted birthday suits.

For the record, anyone who goes to see Crepuscule (which continues its run through Sunday) looking for titillation would be better off to cross the Broadway Bridge and hit the Magic A Go Go or Mary’s Club. For that matter, they’d be better off staying home and watching television commercials.

Skin has seldom seemed as somber as it does here in Leveille’s dance, which somehow manages to seem liberated and stern at the same time, like morning prayers at a Puritan nudist colony.

Skin has seldom seemed as somber as it does here in Leveille’s dance, which somehow manages to seem liberated and stern at the same time, like morning prayers at a Puritan nudist colony.

There are formal issues going on in this dance, and the nakedness serves a function. It’s an extension, I think, of the function that the unfettered human form served for the creators of classical statuary and Romantic painting: a contemplation of the physical fullness of the body, but in this case clear-eyed and unidealized (although, let’s face it, these are dancers’ bodies, and if they’re not exactly Michelangelo’s David they’re still in far better shape than yours and mine).

Mr. Scatter found himself thinking how right it can be that the line of the body is allowed to trace itself in its entirety, not stopping at the small of the back and continuing at high thigh; about how rarely we view reproductive organs in a nonsexualized context. In Crepuscule the body just is. It’s the thing we all walk around in, divested of illusions. It seemed, in this dance, to share something with the nakedness of the original Olympic games, maybe because Leveille’s choreography borrows a lot of movement from martial arts.

Still, nakedness sets off social alarms. There was a time, years ago, when nudity was so common on the stages of Portland that Mr. Scatter, in the course of scurrying from basement to loft in order to comment on productions in the pages of a certain large periodical of august sensibility, sometimes forgot to mention it. It was just the times. An all-nude production of Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit wouldn’t have been entirely surprising.

Thus, this memorable conversation. Since I’ve forgotten the production in question, let’s just slip Coward’s comedy in its place:

Mr. Editor: “Does-so-and-so’s production of Blithe Spirit have nudity in it?”

Mr. Scatter (searching his memory): “Uh … yeah. It does.”

Mr. Editor: “For god’s sake, man, why didn’t you mention it in your review?”

Mr. Scatter (sensing something has gone amiss): “I dunno. It didn’t seem important, I guess.”

Mr. Editor: “Not bloody important! A friend of [here, fill in the name of a high muckamuck editor of the time] went to see it after reading your review, and she was so horrified she complained to him!”

Mr. Scatter: “Well, I suppose it could be a shock to people who don’t go to the theater very often …”

Mr. Editor: “Those are our readers! And they deserve to know what they’re getting into, for crying out loud.”

Mr. Scatter: “Uh … that’s a good point, I guess …”

Mr. Editor (sarcastically): “A good point! Let me put it this way. When [high muckamuck editor] finds out from a friend that Madame Arcati doesn’t have her clothes on and we didn’t report it, he is not a happy man. When [high muckamuck editor] is unhappy he makes me unhappy. And when I’m unhappy I make you unhappy. So let’s make this clear. If they bloody take their shirts off, say so in the bloody review. Clear?”

Mr. Scatter (chastened): “Clear.”

And the warning signs started popping up in Mr. Scatter’s reviews, although usually without parsing whether the nudity was full or partial.

Gradually the times changed, too, and the postings became less necessary. When a revival of Hair came along and the young performers left themselves demurely, sweetly draped, it was clear that the culture had undergone a shift.

Apparently, with Leveille’s Twilight of the Oceans, it’s now undergoing a sea shift. Still, you’ll note, we’ve pointed out the nudity.

****************

Illustrations, from top:

- Emmanuel Proulx spins Mathieu Campeau in one of the signature moves of “Crepescules des Oceans.” Photo: Denis Farley. Daniel Leveille Danse.

- (Almost) full monty in the Garden of Eden. Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553): “Adam and Eve.” Beech wood, 1533. Bode-Museum, Berlin (Erworben 1830, Königliche Schlösser, Gemäldegalerie Kat. 567). Wikimedia Commons.

- How full is partial? Painting from Manafi al-Hayawan (“The Useful Animals”), depicting Adam and Eve. From Maragh in Mongolian Iran, ca. 1294-99. Wikimedia Commons.

Last night at Mississippi Studios, where six of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s dancers were performing the first of three nights of a sweet little show that company soloist Candace Bouchard whipped up in a couple of weeks, I couldn’t help thinking about George Balanchine.

Last night at Mississippi Studios, where six of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s dancers were performing the first of three nights of a sweet little show that company soloist Candace Bouchard whipped up in a couple of weeks, I couldn’t help thinking about George Balanchine. Rather, because history is to some degree repeating itself.

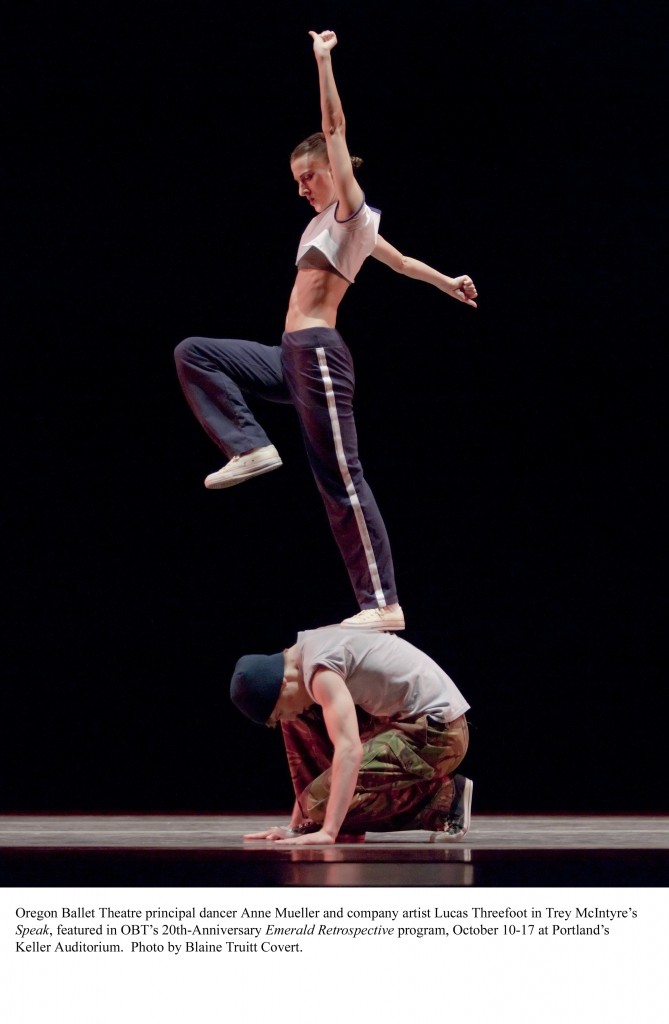

Rather, because history is to some degree repeating itself. OBT’s dancers are not starving, and they’re not coping with food shortages caused by a revolution, although they are calling a projected series of performances in nontraditional spaces Uprising. This program, which repeats tonight and tomorrow, is the first. But Bouchard, soloists Stephen Houser and Ansa Deguchi, and company artists Leta Biasucci, Olga Krochik and Lucas Threefoot have been off-contract at OBT since the Emeralds season-opener, and they are definitely dancing to put food on their tables.

OBT’s dancers are not starving, and they’re not coping with food shortages caused by a revolution, although they are calling a projected series of performances in nontraditional spaces Uprising. This program, which repeats tonight and tomorrow, is the first. But Bouchard, soloists Stephen Houser and Ansa Deguchi, and company artists Leta Biasucci, Olga Krochik and Lucas Threefoot have been off-contract at OBT since the Emeralds season-opener, and they are definitely dancing to put food on their tables. And dancing very well, to a large degree because they were dancing to live music, the often infectious beat produced by the indie folk band Horse Feathers.

And dancing very well, to a large degree because they were dancing to live music, the often infectious beat produced by the indie folk band Horse Feathers. Bouchard, whose goal was to make classical ballet user-friendly, did not patronize her audience. Incorporated into the choreography were difficult fifth positions and some complicated lifts.

Bouchard, whose goal was to make classical ballet user-friendly, did not patronize her audience. Incorporated into the choreography were difficult fifth positions and some complicated lifts. It’s a generous performance, danced with the same heart these dancers put into their OBT work, and the close quarters of Mississippi Studios give even seasoned ballet-goers a fresh perspective on the dancers’ talent. Company dancer Grace Shibley was represented by some simple costumes, incidentally, in which the dancers could move well, although I could have done without the spangles on Houser’s vest.

It’s a generous performance, danced with the same heart these dancers put into their OBT work, and the close quarters of Mississippi Studios give even seasoned ballet-goers a fresh perspective on the dancers’ talent. Company dancer Grace Shibley was represented by some simple costumes, incidentally, in which the dancers could move well, although I could have done without the spangles on Houser’s vest.

His pride in Dance Project artistic director Sarah Slipper’s new work, Not I, is justified. While I wish I had known when I was watching Andrea Parsons perform this very demanding and emotion-laden solo that the monologue she was dancing to was the uncredited Samuel Beckett’s — and while the video monitor on stage was a bit too reminiscent of Bill T. Jones’s controversial Still/Here, which also dealt with bodies raddled by illness and minds sinking into dementia — Slipper’s jitter-laden, despairing movement has stayed with me. And it’s passed this sure test: I’d like to see it again. Moreover, it was the only piece on this program that had a discernible beginning, middle and end.

His pride in Dance Project artistic director Sarah Slipper’s new work, Not I, is justified. While I wish I had known when I was watching Andrea Parsons perform this very demanding and emotion-laden solo that the monologue she was dancing to was the uncredited Samuel Beckett’s — and while the video monitor on stage was a bit too reminiscent of Bill T. Jones’s controversial Still/Here, which also dealt with bodies raddled by illness and minds sinking into dementia — Slipper’s jitter-laden, despairing movement has stayed with me. And it’s passed this sure test: I’d like to see it again. Moreover, it was the only piece on this program that had a discernible beginning, middle and end.

The Portland Art Museum, in a show assembled by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, heralds the arrival of China Design Now. (“Now” is really then, but a recent then: The show was aimed to coincide with last year’s Beijing Olympics and to capture the wave of commercial and aesthetic design in the world’s most populous country, a wave that inevitably has since washed on.)

The Portland Art Museum, in a show assembled by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, heralds the arrival of China Design Now. (“Now” is really then, but a recent then: The show was aimed to coincide with last year’s Beijing Olympics and to capture the wave of commercial and aesthetic design in the world’s most populous country, a wave that inevitably has since washed on.) I remember that film well — the extreme, almost ecstatic enthusiasm of China’s musicians; Stern’s encouragement and good will; his sense that the older students and musicians he encountered — the ones who’d spent years being “reeducated” in peasant labor and cut off from contact with Western music — seemed technically correct but lacking passion in their playing.

I remember that film well — the extreme, almost ecstatic enthusiasm of China’s musicians; Stern’s encouragement and good will; his sense that the older students and musicians he encountered — the ones who’d spent years being “reeducated” in peasant labor and cut off from contact with Western music — seemed technically correct but lacking passion in their playing.

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!”

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!” Jon Ulsh, the embattled executive director, is out. Artistic director Christopher Stowell picks up some of his role, and chief operating officer Doug Wells will assume day-to-day management. The Oregonian’s Barry Johnson

Jon Ulsh, the embattled executive director, is out. Artistic director Christopher Stowell picks up some of his role, and chief operating officer Doug Wells will assume day-to-day management. The Oregonian’s Barry Johnson

WORDSTOCK. Portland’s annual writers’ frenzy heads into its big weekend at the Oregon Convention Center with talks, workshops and publishers’ booths Saturday and Sunday. About a zillion Northwest writers will join such A-list types as James Ellroy and Sherman Alexie. Jeff Baker ran

WORDSTOCK. Portland’s annual writers’ frenzy heads into its big weekend at the Oregon Convention Center with talks, workshops and publishers’ booths Saturday and Sunday. About a zillion Northwest writers will join such A-list types as James Ellroy and Sherman Alexie. Jeff Baker ran