Update: After posting this I ran into Jon Ulsh, OBT’s executive director, who pointed out that OBT isn’t cutting all live music: There’ll be some, but not the full orchestra. That’s an important distinction. Even a pair of pianists can make a huge difference, as OBT’s recent premiere of Christopher Stowell’s version of The Rite of Spring showed so satisfyingly. Cutting the full orchestra, Ulsh said, saved $300,000. That still left $1.7 million to cut elsewhere. After explaining the cuts, he excused himself. “I’ve got to go raise some money,” he said.

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected: Oregon Ballet Theatre, faced with tumbling income because its ordinary donors don’t have the money to give anymore, is slashing its budget by 28 percent. That’s an overnight cut from $6.7 million to $4.8 million, as Grant Butler reports in The Oregonian.

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected: Oregon Ballet Theatre, faced with tumbling income because its ordinary donors don’t have the money to give anymore, is slashing its budget by 28 percent. That’s an overnight cut from $6.7 million to $4.8 million, as Grant Butler reports in The Oregonian.

These are the times we live in, and Scatter partner Barry Johnson talks about their effect on the city’s arts scene in his Portland Arts Watch column this morning on The Oregonian’s Web site, Oregon Live.

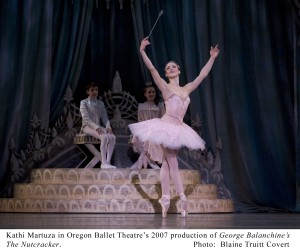

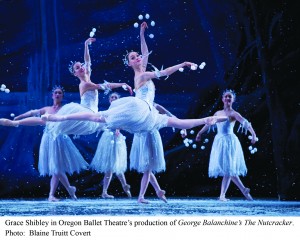

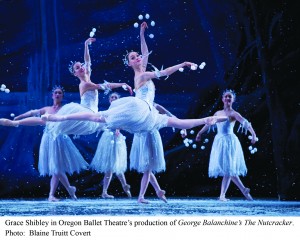

Oregon Ballet Theatre is very good: This rising company has been making a genuine mark nationally. But in today’s shell-shocked economy it’s not enough to be good. You also have to have a cushion. And that, OBT does not have. It has no endowment, and its always-thin budget is brittle to the point of breaking. Butler reports that the number of full-time dancers will drop from 28 to 25, which isn’t precipitous, although none of these dancers is exactly striking it rich, and three more high-quality artists will now be out of work.

As troubling from an artistic view is the sacrifice of live music for at least the next season. Maybe that doesn’t seem like such a big deal — maybe the world of contemporary dance has got you used to the idea of canned music — but they call it “canned” for a reason: It’s prepackaged, unchanging, from a dancer’s view metronomic, or at least predictable: It doesn’t have the edge that live musicians supply. Ballet thrives in the thrilling uncertainty of the moment, when conductor and musicians and dancers all respond to the others in real time and everyone’s attention is heightened. Great ballet requires live musicians. Now, the dozens of talented musicians who make up this orchestra are out of a job, too.

Live music, including full orchestration, has been one of the prime aspirations and foundations of Christopher Stowell’s vision for this company since he took over as artistic director. I’m sure he hasn’t changed that determination. But he’s had to put it on hold. Sometimes being able to establish a holding pattern is a triumph. At least for now, this is putting the brakes on a company that was going places. Now, it’s hunker down and survive.

*****

If a recession or a depression is something that we think ourselves into, maybe it’s something we think ourselves out of, too. For years it’s been obvious that both Oregon Ballet Theatre and Portland Opera need a better place to perform. Although both dip occasionally into the 900-seat Newmark Theatre, home base for both companies is the cavernous, 3,000-seat Keller Auditorium, a hall that puts performers and audiences alike at a disadvantage. It’s too big; it swallows sight and sound.

Over the past year I’ve talked a few times unofficially with the ballet’s Stowell and Portland Opera’s general dirctor, Christopher Mattaliano, about the possibilities of creating a new theater for the two companies to share — something actually designed for the art forms rather than as an all-purpose barn, which is essentially what Keller Auditorium is. Stowell and Mattaliano happen to get along very well, and for the long-term health of both companies, both men would love to see this happen.

A new hall would be as intimate as the economics of the business would allow it to be — somewhere between 1,400 and 2,400 seats, and if that seems like a wide range, it is: There’s plenty of room for honing this dream. It could also encourage other partnerships: the development of a full-time orchestra for the ballet and opera to share; combined marketing; even (and this last part is me speaking, not Stowell or Mattaliano) combined administrative and fund-raising services.

Is this a crazy time to be bringing this sort of thing up? Yes, and no. Obviously nobody’s going to start a bricks-and-mortar campaign now, with the economy circling into the sewer. Portland Center Stage is still roughly 9 million bucks short of paying off its move to the Armory, for crying out loud, and the meter seems stuck on that one.

But I keep remembering that Portland voters approved construction of the Portland Center for the Performing Arts in the midst of the city’s last bad recession, in the early 1980s, when the city’s and state’s economies weren’t as diverse as they are now. Sometimes people think biggest when things look the worst. And I know that if you don’t have goals even in the toughest of times, you won’t get anywhere. Call this one a dream deferred — temporarily.

*****

On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian, here.

On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian, here.

The puppet company Night Shade was performing at Disjecta, the warehouse-like arts space in the shadow of the Paul Bunyan statue that marks the rapidly reviving Kenton district (a revival sparked partly by the Interstate MAX light-rail line). The district does have its holdovers, which is part of its charm, and one of them is a strip club across from Disjecta called the Dancin’ Bare.

Here’s what the club’s reader board said:

Amature Night

Hot Girls Cold Beer

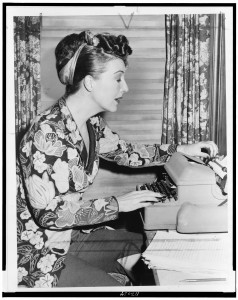

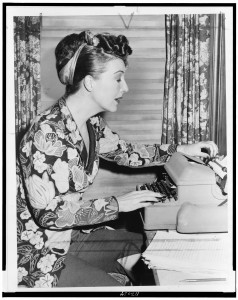

Well, Gypsy Rose Lee was a literary-minded stripper (note her firm familiarity with the keyboard in the photo) and I can’t imagine that in the heyday of burlesque she’d have put up with a misspelling as glaring as that, any more than she’d have put up with any amateurs horning in on her profession.

And when Gypsy Rose danced, she danced to live music.

*****

Quick links: I’ve also been hitting the galleries lately, and have a couple of reviews in this morning’s Oregonian. The print-edition reviews are briefs. You can find the longer versions online at Oregon Live:

— Photographer Paul Dahlquist’s 80th-birthday show at Gallery 114, and photos by Terry Toedtemeier from the 1970s, at Blue Sky. Review here.

— Glass art by Steve Klein and Michael Rogers at Bullseye Gallery. Review here.

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected:

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected:  On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian,

On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian,

God knows Stravinsky’s 1912 Sacre du Printemps, played brilliantly here in its two-piano version by Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, is structured. Its lyrical beginning builds to a pounding crescendo in music that is still startling for its highly stylized brutality.

God knows Stravinsky’s 1912 Sacre du Printemps, played brilliantly here in its two-piano version by Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, is structured. Its lyrical beginning builds to a pounding crescendo in music that is still startling for its highly stylized brutality.