UPDATE: Barry Johnson takes the story further on his Oregonian blog, Portland Arts Watch, with this post on Friday. This appears to be very much a hot issue. Keep watching Portland Arts Watch.

Ever since last spring’s remarkable bailout from its equally remarkable tumble down the financial rabbit hole, Oregon Ballet Theatre has been trying to assure everyone that things are really OK now — and rumors have been rumbling that they most decidedly are not.

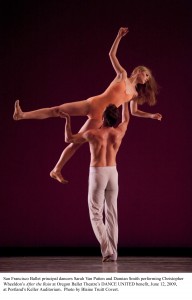

Bet on the latter. Willamette Week’s Kelly Clarke reported online Thursday that 41 members of the company — including many of the dancers, highly respected school chief Damara Bennett, ballet master Lisa Kipp and artistic director Christopher Stowell’s executive assistant, Rebecca Roberts — have signed a letter to the board asking for reviews of the leadership of both Stowell and executive director Jon Ulsh. Our good friend Barry Johnson joined in with this report on his Portland Arts Watch blog for The Oregonian. Do read them both to understand the background.

Although Stowell’s name is mentioned, it seems clear that Ulsh is the focus of what amounts to an anguished cry from the ballet’s rank and file — a mutiny, almost, in a business that takes its traditional hierarchy as a matter of fact.

“Either (Ulsh) does not have the skill set” to deal with the multiple challenges of his job, the letter stated, “or he does not have the capacity to handle all of them at once. It seems to me that if he did, we would not be in such deep difficulty after three years under his leadership.” The letter, composed by company historian Linda Besant, continues: “… I do not feel that the organization can afford to be a training ground for its executive director in this very crucial year.â€

Harsh words. And it seems odd that they were written by someone as relatively on the sidelines as the company historian. You could dismiss it as internal grumbling except that so many major players took the extraordinary step of signing it, potentially putting their own jobs on the line.

Harsh words. And it seems odd that they were written by someone as relatively on the sidelines as the company historian. You could dismiss it as internal grumbling except that so many major players took the extraordinary step of signing it, potentially putting their own jobs on the line.

I want to make it very clear that I haven’t talked with Ulsh, Stowell, or any member of the board about OBT’s administrative troubles since the letter was sent. My thoughts are based on the news reports I’ve read, past observations, and second-hand reports from people close to the scene. I’m hoping to start a conversation here, not end one, and I hope people inside the company will feel free to respond openly.

It seems telling that while the actual artists in the ballet company are underpaid and thus prone to unrest, so are the musicians in the Oregon Symphony — and from what I can tell, most of the symphony musicians, who have accepted stiff pay cuts and reductions in benefits to help cope with the orchestra’s own fiscal troubles, are solidly behind their leaders, music director Carlos Kalmar and and president Elaine Calder.

So what’s the difference?

Hard to say, except it appears that while the symphony musicians have faith in Calder’s efforts to rethink how the orchestra presents itself to the community, a significant and perhaps majority percentage of the ballet dancers and staff have no such faith in Ulsh’s abilities. The letter, in fact, amounted to a vote of no confidence in Ulsh’s ability to carry out his duties.

Is there an element of scapegoating here? I don’t know. Maybe. I do recall that after the ballet’s emergency call last spring to raise $750,000 to keep it from folding (an astonishing outpouring of generosity brought in more than $900,000) one person extremely close to the company told me, “There’s going to be a scapegoat for this, and it’s going to be Jon Ulsh.”

And here we are. I’ve heard other theories, as dark and murky as a Dan Brown book plot, circling: Ulsh has stacked the board with his own supporters, and Stowell will take the fall. I see no evidence of that. I’ve known Ulsh casually for several years, and he seems both an honorable and an earnest man — and as even Besant notes in her letter, a man committed to the company’s success. Stowell has gained deserved recognition nationally for transforming this small company into a rising force in the American ballet world, and if the board doesn’t understand that, it ought to just give up the ghost and disband. Boards aren’t social clubs. They have strict duties, and the first is to understand the nature of the organization they oversee. The nature of this organization is this: Stowell has reshaped it into one of the most exciting small ballet companies in the nation. Period.

So what’s the trouble? M-O-N-E-Y.

No surprise there. Nonprofit organizations across the country, from museums to major universities, are in deep trouble, and sometimes because they got caught up in the go-go Wall Street frenzy themselves, as Stephanie Strom reported in the New York Times today. That’s surely no problem in Portland, where no nonprofit I know of has enough money in reserve to play the market. Arts groups here are in trouble (partly) because of the market, not because they play the market.

OBT spent some months last year without a development director — a crucial position in a company of the ballet’s size. I asked a board member over the summer how the company was approaching fund-raising. It wouldn’t have a development director, he told me: That was one of the positions cut in the ballet’s budget belt-tightening. Then how are you going to raise money? I asked. Ulsh and Stowell will do it themselves, he replied. Most big donors want to talk with the artistic director, anyway: It’s a big part of his job.

True enough. But the artistic-director shmooze is supposed to seal the deal, not start it. He’s the artistic director, after all, and while pragmatics dictate that he or she has a role in bringing in the bucks, other people (including the board) have to do the major hauling.

I noted with both optimism and pessimism that when the ballet raised more than $900,000 in its emergency drive last spring, no single donation was over $25,000. That meant a huge number of people were sending in their $10, $50, $250 checks. It also meant the big-bucks crowd was keeping its pockets buttoned — and no arts group can hope to thrive in the long term without some deep-pocket supporters. Where are OBT’s deep pockets? And if they don’t exist, why not? I don’t know.

This maybe-divorce proceeding is also significant because, in a sense, OBT has seemed reborn since its emergency bailout in the spring. The company seems to have rediscovered that it’s part of a local community, and that that’s a good thing. OBT dancers have been all over town, taking part in events by other companies, dancing and choreographing in fund-raising events for the beleaguered contemporary-dance center Conduit. Stowell’s been everywhere, shaking hands, giving talks, supporting other groups, being part of things. People have begun to feel that the ballet is connected, and they’ve appreciated it. Why risk that good will? Apparently, because so many members of the company feel it’s necessary.

On a personal level, I want to be very clear here. The rise of OBT to its current level of performance has been one of the most encouraging and thoroughly pleasing arts stories that I’ve covered in the past 15 years. I would be devastated if this gutsy, talented, polished, personality-laden company lost the momentum it’s worked so hard to achieve.

In July I was talking on other matters with Paul Nicholson, executive director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, which has seen a steep decline in its own endowment but has maintained its institutional stability. The subject of OBT’s recent bailout came up.

“A crisis is a terrible thing to waste,” Nicholson told me. “And it would be a shame if Oregon Ballet Theatre did not take this and use it as a springboard to build those stronger relationships with those donors. If they just said, ‘Thank you very much,’ and that was the end of it. … Think of the incredible data base they’ve now compiled. There’s not much more signal that those donors can send to the theater that they care.â€

A whole lot of people care, deeply. Can we now please try to solve this thing?

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!”

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!” Jon Ulsh, the embattled executive director, is out. Artistic director Christopher Stowell picks up some of his role, and chief operating officer Doug Wells will assume day-to-day management. The Oregonian’s Barry Johnson

Jon Ulsh, the embattled executive director, is out. Artistic director Christopher Stowell picks up some of his role, and chief operating officer Doug Wells will assume day-to-day management. The Oregonian’s Barry Johnson

WORDSTOCK. Portland’s annual writers’ frenzy heads into its big weekend at the Oregon Convention Center with talks, workshops and publishers’ booths Saturday and Sunday. About a zillion Northwest writers will join such A-list types as James Ellroy and Sherman Alexie. Jeff Baker ran

WORDSTOCK. Portland’s annual writers’ frenzy heads into its big weekend at the Oregon Convention Center with talks, workshops and publishers’ booths Saturday and Sunday. About a zillion Northwest writers will join such A-list types as James Ellroy and Sherman Alexie. Jeff Baker ran

Harsh words. And it seems odd that they were written by someone as relatively on the sidelines as the company historian. You could dismiss it as internal grumbling except that so many major players took the extraordinary step of signing it, potentially putting their own jobs on the line.

Harsh words. And it seems odd that they were written by someone as relatively on the sidelines as the company historian. You could dismiss it as internal grumbling except that so many major players took the extraordinary step of signing it, potentially putting their own jobs on the line.

Surely a heavy price to pay — and the pizza was good, too. For several years

Surely a heavy price to pay — and the pizza was good, too. For several years

The intrepid Mighty Toy Cannon has the story at Culture Shock;

The intrepid Mighty Toy Cannon has the story at Culture Shock;  While Art Scatter was spending Thursday in the Columbia Gorge visiting the

While Art Scatter was spending Thursday in the Columbia Gorge visiting the  Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans. The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process. The smashing success of last Friday’s

The smashing success of last Friday’s