Remember the old days, when Cadillac-sized opera singers planted their feet among the scenery and belted beautiful music with no thought to the dramatic possibilities of the opera? Art Scatter’s senior correspondent Martha Ullman West does, and she shudders at the memory. What’s more, she sees the old style’s residual effects in the staging of “Orphee” at Portland Opera. Her message: Pay attention to the dancemakers. They have lessons for the musical stage.

Philip Cutlip as Orphee and Lisa Saffer as La Princesse. photo: Cory Weaver/Portland Opera

First the disclaimer — my opera expertise is limited, although my opera attendance began when I was 10 when my father took me to a New York City Opera production of The Marriage of Figaro. I really got the bug when I was in college, and for the past 35 years or so I’ve been an off and on subscriber to the Portland Opera.

So I belong to a generation of opera-goers that has seen a paradigmatic shift in staging: Gone, mostly, are the days when Licia Albanese, say, as the tragic Butterfly, planted her feet, opened her mouth and sang (in heavenly fashion, I might add) her concluding aria; or Pavarotti, as the lascivious duke in Rigoletto, did the same. Today, opera singers have to be able to move. Body language is part of the art form.

And in a Philip Glass opera, they ought to be able to move a lot more dynamically than they were directed to do in Orphee, which I saw Sunday afternoon. In all other respects I thought Portland Opera’s production was stunning, from the score, to the conducting, to the set, to the singing, particularly by Philip Cutlip as Orphee, Georgia Jarman as Eurydice and Lisa Saffer as the Princess.

BUT, my esteemed colleague David Stabler complained in The Oregonian that the production was static, and he’s right. Only Cutlip and Jarman seemed really physically at ease onstage, moving naturally, and with a certain amount of impulse. Saffer did indeed prowl from time to time, but that’s all she did, except to smoke, and everyone else moved stiffly and self-consciously, when they moved at all, except for a bit of leaping on and off of sofas and the bar in the party scene.

I couldn’t help thinking how different it would have looked if it had been directed by Jerry Mouawad in the way he staged No Exit for Imago. In fact, speaking of French poets, are we in Portland this fall enjoying a Season in Hell? (That’s Rimbaud’s long poem, and come to think of it, it would make a dandy opera.)

Glass deserves better physical direction for his operas. He has collaborated with a lot of choreographers. In fact, the first review I did for Dance Magazine, in 1979 (an essay review on post-modern dance in New York) included the premiere of DANCE, a piece he did with Lucinda Childs, which included elegant film images and for which he performed accompaniment himself.

Continue reading A dance critic at the opera: Move it, singers!

Last night at Mississippi Studios, where six of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s dancers were performing the first of three nights of a sweet little show that company soloist Candace Bouchard whipped up in a couple of weeks, I couldn’t help thinking about George Balanchine.

Last night at Mississippi Studios, where six of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s dancers were performing the first of three nights of a sweet little show that company soloist Candace Bouchard whipped up in a couple of weeks, I couldn’t help thinking about George Balanchine. Rather, because history is to some degree repeating itself.

Rather, because history is to some degree repeating itself. OBT’s dancers are not starving, and they’re not coping with food shortages caused by a revolution, although they are calling a projected series of performances in nontraditional spaces Uprising. This program, which repeats tonight and tomorrow, is the first. But Bouchard, soloists Stephen Houser and Ansa Deguchi, and company artists Leta Biasucci, Olga Krochik and Lucas Threefoot have been off-contract at OBT since the Emeralds season-opener, and they are definitely dancing to put food on their tables.

OBT’s dancers are not starving, and they’re not coping with food shortages caused by a revolution, although they are calling a projected series of performances in nontraditional spaces Uprising. This program, which repeats tonight and tomorrow, is the first. But Bouchard, soloists Stephen Houser and Ansa Deguchi, and company artists Leta Biasucci, Olga Krochik and Lucas Threefoot have been off-contract at OBT since the Emeralds season-opener, and they are definitely dancing to put food on their tables. And dancing very well, to a large degree because they were dancing to live music, the often infectious beat produced by the indie folk band Horse Feathers.

And dancing very well, to a large degree because they were dancing to live music, the often infectious beat produced by the indie folk band Horse Feathers. Bouchard, whose goal was to make classical ballet user-friendly, did not patronize her audience. Incorporated into the choreography were difficult fifth positions and some complicated lifts.

Bouchard, whose goal was to make classical ballet user-friendly, did not patronize her audience. Incorporated into the choreography were difficult fifth positions and some complicated lifts. It’s a generous performance, danced with the same heart these dancers put into their OBT work, and the close quarters of Mississippi Studios give even seasoned ballet-goers a fresh perspective on the dancers’ talent. Company dancer Grace Shibley was represented by some simple costumes, incidentally, in which the dancers could move well, although I could have done without the spangles on Houser’s vest.

It’s a generous performance, danced with the same heart these dancers put into their OBT work, and the close quarters of Mississippi Studios give even seasoned ballet-goers a fresh perspective on the dancers’ talent. Company dancer Grace Shibley was represented by some simple costumes, incidentally, in which the dancers could move well, although I could have done without the spangles on Houser’s vest.

His pride in Dance Project artistic director Sarah Slipper’s new work, Not I, is justified. While I wish I had known when I was watching Andrea Parsons perform this very demanding and emotion-laden solo that the monologue she was dancing to was the uncredited Samuel Beckett’s — and while the video monitor on stage was a bit too reminiscent of Bill T. Jones’s controversial Still/Here, which also dealt with bodies raddled by illness and minds sinking into dementia — Slipper’s jitter-laden, despairing movement has stayed with me. And it’s passed this sure test: I’d like to see it again. Moreover, it was the only piece on this program that had a discernible beginning, middle and end.

His pride in Dance Project artistic director Sarah Slipper’s new work, Not I, is justified. While I wish I had known when I was watching Andrea Parsons perform this very demanding and emotion-laden solo that the monologue she was dancing to was the uncredited Samuel Beckett’s — and while the video monitor on stage was a bit too reminiscent of Bill T. Jones’s controversial Still/Here, which also dealt with bodies raddled by illness and minds sinking into dementia — Slipper’s jitter-laden, despairing movement has stayed with me. And it’s passed this sure test: I’d like to see it again. Moreover, it was the only piece on this program that had a discernible beginning, middle and end.

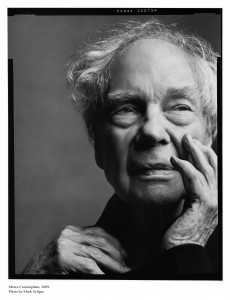

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche. By MARTHA ULLMAN WEST

By MARTHA ULLMAN WEST

The show began with TouchMonkey, in the persons of Carolyn Stuart and Patrick Gracewood, who are longtime practitioners of Contact Improvisation, a form based on trust and the ability to make on-the-spot kinetic connections. Stuart was wearing a black cloth over her eyes, which meant her responses to Gracewood were entirely by touch and contact. Their duet, titled Special Alembics, (nice pun!) was performed to music played live by Eddy Deane, Alley Teach, and David Lyles of The Contact Lounge Band.

The show began with TouchMonkey, in the persons of Carolyn Stuart and Patrick Gracewood, who are longtime practitioners of Contact Improvisation, a form based on trust and the ability to make on-the-spot kinetic connections. Stuart was wearing a black cloth over her eyes, which meant her responses to Gracewood were entirely by touch and contact. Their duet, titled Special Alembics, (nice pun!) was performed to music played live by Eddy Deane, Alley Teach, and David Lyles of The Contact Lounge Band.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans. The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process. THE LATEST NEWS FROM OREGON BALLET THEATRE, which is struggling with a life-threatening deficit that has it feverishly trying to raise $750,000 by June 30 to keep from going out of business: The campaign hit the $524,000 mark by Wednesday. That morning OBT’s Erik Jones said 900 tickets were still available for Friday night’s gala benefit performance Dance United, which will bring star performers from across North America to raise money for OBT. Buy your tickets

THE LATEST NEWS FROM OREGON BALLET THEATRE, which is struggling with a life-threatening deficit that has it feverishly trying to raise $750,000 by June 30 to keep from going out of business: The campaign hit the $524,000 mark by Wednesday. That morning OBT’s Erik Jones said 900 tickets were still available for Friday night’s gala benefit performance Dance United, which will bring star performers from across North America to raise money for OBT. Buy your tickets  OBT’s season-finale program was designed to accomplish several goals, one of which was to challenge the dancers. And there is no getting around the fact that the work those dancers had performed most often — Rush, Afternoon of a Faun and The Concert — was polished to the accomplished shine you see only in major companies: New York City Ballet, San Francisco Ballet, Pacific Northwest Ballet, Houston Ballet and the like. These are troupes with far bigger budgets, many more dancers and far more opportunities to perform than OBT.

OBT’s season-finale program was designed to accomplish several goals, one of which was to challenge the dancers. And there is no getting around the fact that the work those dancers had performed most often — Rush, Afternoon of a Faun and The Concert — was polished to the accomplished shine you see only in major companies: New York City Ballet, San Francisco Ballet, Pacific Northwest Ballet, Houston Ballet and the like. These are troupes with far bigger budgets, many more dancers and far more opportunities to perform than OBT.